As the final curtain falls on Bradford's landmark year as UK City of Culture, the city's creative director, Shanaz Gulzar, is reflecting on a monumental programme. The year saw more than 5,000 events take place and an estimated £51 million spent, making it the largest City of Culture programme since the scheme's inception in 2013.

A Year of Empowerment and Hyper-Local Investment

For Gulzar, the personal highlights were as diverse as the programme itself. They ranged from the freezing opening ceremony, 'Rise', in January to the sprawling musical epic 'The Bradford Progress' and a powerful exhibition of Victor Wedderburn's photographs capturing Black Bradford in the 1980s. Crucially, she notes how audiences saw themselves reflected in the work and how visiting artists developed a newfound affection for the city.

Yet, the celebratory afterglow is tempered by urgent questions about legacy. In a city where around 40% of children live below the poverty line and significant deprivation persists, the year was never touted as a cure-all. However, it provided a vital injection of optimism and a focused, hyper-localised 'levelling up' agenda.

Gulzar points to tangible infrastructure investments totalling £9 million for capital projects—a first for the City of Culture scheme. This funding breathed new life into existing community assets. A prime example is the 1 in 12 Club, an anarchist-run venue open since 1981. An initial £90,000 grant was doubled to address critical issues like faulty fire doors and ageing electrics, with hopes now for a lift installation.

Scepticism and the Challenge of Sustainable Momentum

Not all are convinced the benefits have been evenly felt. Independent councillor Ishtiaq Ahmed questions whether the programme reached beyond traditional arts audiences. "Have we just reached those that were already in the know?" he asks, emphasising that impact shouldn't be limited to the culturally "plugged-in".

His scepticism extends to the long-term view, a concern underscored by the mixed fortunes of past host cities. Hull struggled with momentum after its legacy chief departed, Derry lacked funds for follow-on projects, and Coventry's post-event programme entered administration. The challenge of converting short-term cultural investment into enduring economic and social uplift is stark.

In Bradford, the physical signs of need remain visible. Next to the new Darley Street Market, tents and empty shop units persist, highlighting the city's battle with homelessness and a vacancy rate higher than the national average.

The Intangible Legacy: Hope and a New Chant

Perhaps the most significant legacy is intangible. Evie Manning of Common Wealth theatre notes how the year challenged a pervasive local narrative of inferiority. "When you grow up here, you really do believe it's the worst place in the UK," she says, arguing that 2025 has fostered a new sense of pride for a younger generation.

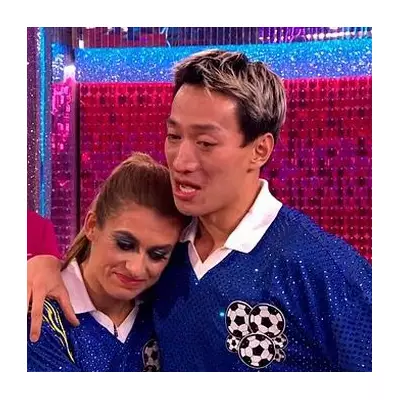

This shift permeates the community in unexpected ways. Members of the 'Bantam of the Opera' choir, formed during the culture year, report a new chant echoing from the stands of Bradford City football matches: "City of culture you'll never sing that." For choir member Jane Gray, the year instilled a "sense of hope and possibility." She describes the closing ceremony as "very empowering," perfectly summarising a year focused on looking forward.

The immediate future includes cultural projects funded until 2027 via the Bradford Culture Company, and hopes that the temporary Loading Bay venue will become a permanent mid-sized space. The delayed opening of the 3,500-capacity Bradford Live adds to a suddenly abundant—if unproven—venue scene.

The ultimate question lingers: can a city not used to abundance sustain this new cultural muscle and optimism? The answer will determine whether 2025 was a spectacular one-off or the true beginning of Bradford's rise.