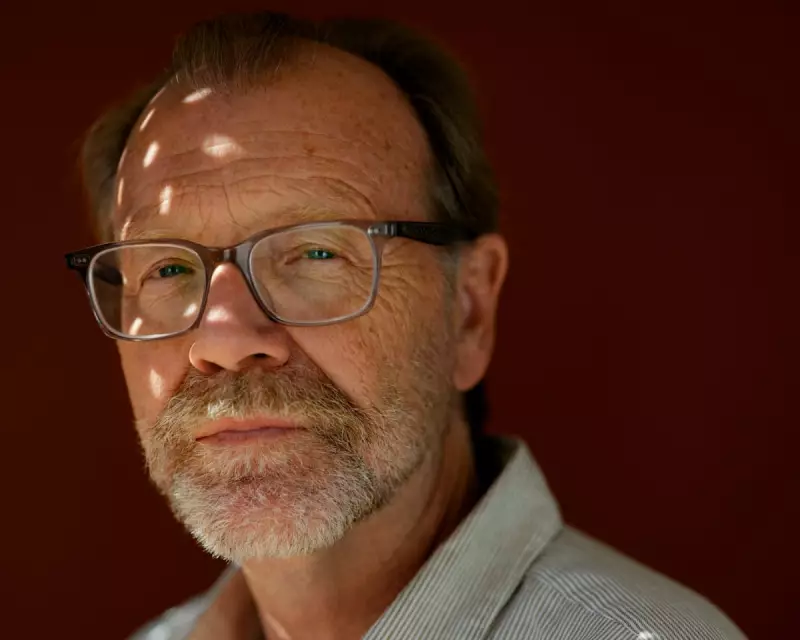

George Saunders makes a spectral return to the literary stage with his latest novel, Vigil, his first major work since the Booker Prize-winning triumph of Lincoln in the Bardo in 2017. Once again, the celebrated author transports readers into that ambiguous, liminal space between life and death, where comedy intertwines with profound grief and moral inquiry dances with narrative mischief. The living remain largely absent from this realm, replaced by meddlesome, chatty ghosts with unresolved grievances and urgent missions.

A Dying Tycoon and His Spectral Visitors

The narrative converges at the deathbed of KJ Boone, a postwar bootstrapper who has amassed immense wealth and lived a long, self-satisfied life. Boone embodies the archetype of the untroubled capitalist, facing his final hours with enviable calm, seemingly destined to depart this world without a flicker of self-reflection. However, as his physical body weakens, his mind becomes strangely permeable to supernatural visitors.

These ghosts have a specific purpose: to confront Boone about his lucrative career built on climate denial and the exploitation of fossil fuels. There remains a narrow window of opportunity for the tycoon to acknowledge his role in environmental destruction before the final curtain falls. The central question becomes whether genuine repentance is possible for a man who has profited so handsomely from planetary harm.

The Death Doula's Dilemma

Our guide through this ethereal drama is Jill Blaine, a spectral death doula who has expertly shepherded hundreds of souls through their final transitions. Her proficiency stems, in part, from the traumatic and explosive nature of her own demise, for which she received no such guidance. Boone presents her most challenging case yet—a thorny, unrepentant individual utterly convinced of his own brilliance and superiority to the "mere earthlings" he considers beneath him.

This scenario forces Jill, and by extension the reader, to grapple with complex ethical questions. What is the true role of a death doula when faced with a figure of such destructive legacy? Should her priority be to comfort the dying, or to correct the moral record? The novel probes the fine line where mercy might shade into complicity, challenging our notions of justice and forgiveness at life's end.

Dickensian Echoes and Modern Disillusionment

Reading Vigil inevitably invites comparison to Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, with its crotchety old miser, ghostly interventions, and a soul hanging in the balance. KJ Boone appears as a potential Anthropocene-era Scrooge. Yet, Saunders crucially departs from the Victorian blueprint. Where Dickens made us root for Scrooge's redemption, offering a radical comfort in the possibility of change, Boone's situation is fundamentally different.

The environmental damage he has helped orchestrate cannot be undone with charitable gestures or sudden benevolence. He has, in the eyes of the narrative and likely the reader, helped to damn the planet. Consequently, the vigil we keep is not one hoping for his salvation, but perhaps anticipating his deserved damnation—a much darker, more modern form of moral reckoning.

Characters and Condemnation

The story introduces us to Boone's contemptuous daughter, who has "recovered from her brief, friend-induced flirtation with libtarditude," and his thoroughly cowed wife. By the time Boone draws his final breath, the novel leaves little room for ambiguity: he is "a bully, a ruiner, an unrepentant world-wrecker." The concept of comeuppance feels hollow and ghoulish, which may be precisely Saunders' point. The moral calculus seems settled; Boone has earned his fate, and even compassion feels like a peculiar form of punishment.

This setup taps into a potent, if simplistic, cultural fantasy: that identifying and eliminating the right corporate villains could somehow balance the global ledger. Billionaires and CEOs make compelling antagonists, some even appearing to relish the role. Yet, as the narrative subtly suggests, felling one such figure often leads to others rising in their place—an economic hydra. The true monstrosity of the climate crisis is its structural, pervasive, and monstrously ordinary nature, lacking a single, satisfying antagonist. Vigil circles this profound idea but struggles to fully escape the gravitational pull of Boone's individual villainy.

The More Compelling Ghost: Jill Blaine

Ironically, the most fascinating character in Vigil is not the dying tycoon but the death doula herself. Jill "Doll" Blaine, in her dedicated service to 343 charges, has performed a profound act of self-erasure, forgetting her own past, her violent end, and even aspects of her identity. As Boone dies, the sounds of a wedding celebration next door pierce her carefully maintained amnesia.

Fragments of her own love story return, but to remember is to relive its catastrophic conclusion. Somewhere, in a lonely attic, her own wedding dress decays—a potent symbol of neglected memory and terrifying loneliness. Saunders suggests that sometimes, forgetting is less painful than remembering. It is in these explorations of Jill's fractured self that the ghosts perform their most persuasive work, not as blunt moral instruments, but as beautifully unfinished souls grappling with their own losses.

From Lincoln's Grief to Boone's Lesson

This stands in contrast to the masterful intimacy of Lincoln in the Bardo, which narrowed the vast scope of history to a single, devastating night—a president holding his dead son. By focusing on the specific, physical weight of grief, Saunders liberated Lincoln from mere allegory, restoring him to the human realm of love and loss. History was present, but its official record was shown to be contradictory; the ultimate, incontrovertible truth was the private, suffocating grief itself.

In Vigil, however, the spectral machinery begins to feel somewhat procedural. The polyphonic chatter, the Beckettian puzzles, the recurring scatological humour (Saunders retains his fondness for gassy, bawdy ghosts and phantom excrement)—what once felt anarchic and fresh now risks hardening into a familiar repertoire of stylistic tics. These devices are deployed to stage a moral lesson for the reader, and the experience can sometimes grate, feeling like confinement within someone else's didactic play—a readerly Bardo of its own.

Vigil by George Saunders is published by Bloomsbury. It presents a haunting, often witty, but ultimately uneasy exploration of guilt, legacy, and the search for accountability in an age of planetary crisis, even as its narrative framework shows signs of strain.