As the celebrated playwright and screenwriter Christopher Hampton celebrates his 80th birthday this month, the National Theatre is preparing a major revival of his most famous work. Les Liaisons Dangereuses, his radical reinvention of the 18th-century French novel, returns to the London stage, casting a spotlight on a dramatist whose career has been defined by a deep fascination with political power play and human contradiction.

The Quiet Man with a Passionate Core

Often described as the quiet man of British theatre, especially when compared to more vocal contemporaries like David Hare, Hampton's work is anything but subdued. His plays are built on the classical virtues of lucidity, irony, and a remarkable objectivity that allows him to see all sides of a conflict. This quality was vividly illustrated in a personal anecdote from November 1990. While on a British Council trip in Cairo, a newly arrived Hampton burst into a hotel in Giza with electrifying news: Margaret Thatcher was under attack in the Commons from Geoffrey Howe, signalling her impending political downfall. The intense passion in his eyes revealed a man deeply engaged with the mechanics of power, a theme that permeates his writing.

Political Power and Clashing Male Egos

Hampton himself has noted that his original plays are fundamentally political, exploring the enduring tension between radicals and liberals. This conflict is frequently personified in clashes between two male protagonists, reminiscent of Peter Shaffer's work but with a distinct Hampton flavour. In his early play Total Eclipse, written in his twenties, he pits the wild genius of Arthur Rimbaud against the cautious orthodoxy of Paul Verlaine, displaying a precocious empathy for both sides. Similarly, his first major hit, The Philanthropist (1970), contrasted an amiable academic with a brutally pragmatic novelist.

The balance of his sympathy shifts from play to play. In Savages (1973), which confronted the genocide of Brazil's Indigenous peoples, his heart seemed to lie more with the local revolutionary than the kidnapped British diplomat. Conversely, in Tales from Hollywood (1983), his alignment leaned towards the liberal writer Ödön von Horváth over the revolutionary Bertolt Brecht, though the production's energy often favoured the disruptive latter. This ability to explore his own internal conflicts allows audiences to confront their own.

Masterful Roles for Women and a Defining Masterpiece

While male conflicts are central, it is a mistake to consider Hampton's female characters subordinate. Plays like Treats feature women skilfully arbitrating between rival lovers, and The Talking Cure (2002) offers a powerful, sympathetic portrait of Sabina Spielrein, who navigated a complex relationship between Freud and Jung. However, his supreme achievement in creating iconic female roles is undoubtedly Les Liaisons Dangereuses.

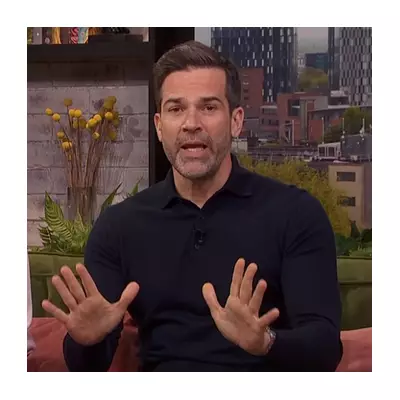

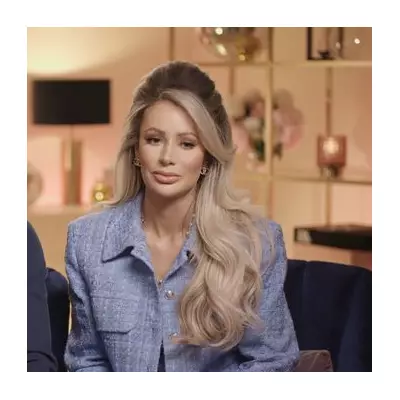

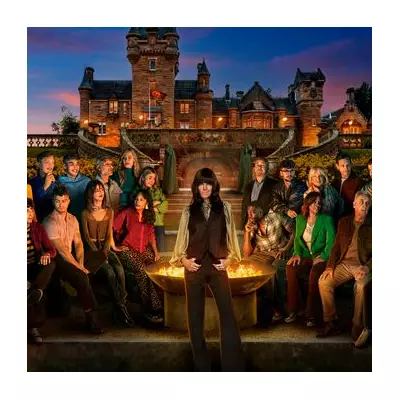

Premiering with the RSC in 1985 and starring Alan Rickman and Juliet Stevenson, the play is far more than a simple adaptation. It is a brilliant theatrical reinvention of the epistolary novel, giving us the coldly demonic Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont. The work meticulously charts the mathematics of seduction and political manoeuvring within the French aristocracy, only to show it all undone by the unstoppable, chaotic force of genuine emotion. As it prepares to open at the National Theatre on 21 March, running until 6 June with a cast including Lesley Manville and Aidan Turner, the revival confirms the play's status as Hampton's masterpiece.

As Christopher Hampton enters his ninth decade, the term 'classical survivor' may suit him better than 'quiet man'. His body of work, from the political explorations of his early plays to the enduring triumph of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, demonstrates a dramatist of enduring power, clarity, and profound insight into the passions that drive both the political and the personal sphere.