The Silent Struggle: Understanding Developmental Coordination Disorder

When a child consistently struggles with basic tasks like tying shoelaces, writing clearly, or maintaining balance during physical education, it's often mistakenly dismissed as mere clumsiness or lack of effort. However, for approximately 5% of children in the UK, these challenges stem from a legitimate neurodevelopmental condition called developmental coordination disorder (DCD), commonly known as dyspraxia.

Groundbreaking research conducted by experts from York St John University, Manchester Metropolitan University, and Oxford Brookes University has uncovered the profound impact this condition has on children's daily lives, educational experiences, and future prospects.

The Diagnostic Delay and Its Consequences

A comprehensive national survey of more than 240 UK parents has revealed a stark reality for families navigating DCD. Despite being as common as ADHD, developmental coordination disorder remains significantly underdiagnosed and poorly understood within both healthcare and educational systems.

Families reported an average waiting period of nearly three years to receive a formal diagnosis, with almost 20% of children displaying clear symptoms but not yet beginning the diagnostic process. While 93% of parents found the diagnosis helpful for understanding their child's difficulties, many expressed frustration that this formal recognition didn't translate into practical support, particularly within school environments.

The movement difficulties associated with DCD create ripple effects throughout children's lives:

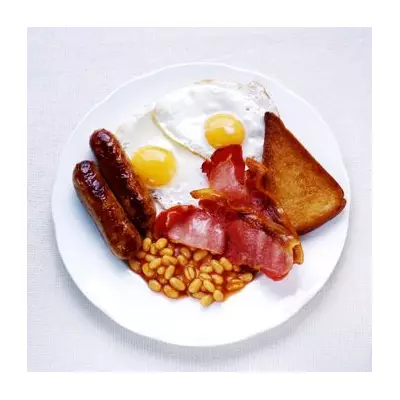

- Daily physical challenges with eating, dressing, using scissors, and handwriting

- Significant fatigue and frustration from routine tasks

- Social exclusion and participation barriers

- Reduced physical activity levels, with only 36% meeting recommended guidelines

The Emotional Toll and Educational Challenges

The emotional impact of DCD proves equally severe, with 90% of parents expressing concern about their child's mental health. Children frequently experience anxiety, diminished self-esteem, and feelings of isolation, with many internalising negative beliefs about their capabilities.

One parent recalled their child asking, "Why do I even try when I'm never picked?" while others shared heartbreaking accounts of children who felt they didn't belong or had concluded they were "stupid" or "terrible."

Within educational settings, support remains inconsistent and often inadequate. Although 81% of teachers were aware of children's motor difficulties, fewer than 60% had implemented individual learning plans. Physical education presented particular challenges, with 43% of parents reporting their children received no support during PE lessons, often encountering teachers who lacked understanding of DCD entirely.

The consequences are significant: 80% of parents believed movement difficulties negatively affected their child's education, with the same proportion concerned about future employment prospects.

The Path Forward: Five Critical Areas for Improvement

Since DCD is a lifelong condition without a current cure, early intervention and appropriate support become crucial for helping children develop management strategies and thrive. Parents and experts have identified five key areas requiring urgent, coordinated action:

Awareness: Nationwide education campaigns targeting the public, schools, and healthcare professionals about DCD's prevalence and characteristics.

Diagnosis: Clear guidance and referral pathways for GPs and frontline professionals to identify early motor difficulties and connect families with support promptly.

Education: Mandatory teacher training in DCD recognition and practical classroom strategies for supporting affected pupils.

Mental Health: Integrated support systems addressing the connection between movement challenges and emotional wellbeing.

Support Access: Early intervention availability without requiring formal diagnosis to prevent long-term harm.

As one parent poignantly noted, "If she can't write her answers down quickly enough in exams, she won't be able to show her knowledge." The cost of neglecting this widespread condition extends beyond academic achievement to the fundamental wellbeing of an entire generation of children struggling in silence.