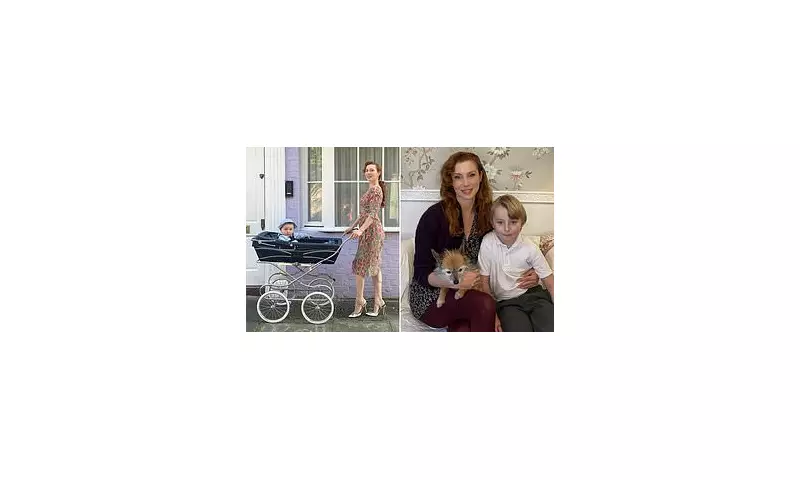

While heavily pregnant and navigating her office corridor, Annette Kellow was handed a surprising gift by an older colleague: a 1950s parenting manual titled Mothercraft. "You'll need this," the colleague muttered, insisting "the old way's the best way." Faced with a deluge of conflicting modern advice online, Annette decided to take the vintage book's robust approach to heart, using it to raise her son, Felix, now seven, in a bid to avoid what she sees as the pitfalls of contemporary, permissive parenting.

Rejecting Modern Martyrdom for Vintage Discipline

Overwhelmed by the sheer volume of parenting guidance and the rise of gentle parenting—a trend with over 287,000 videos on TikTok alone—Annette found the Mothercraft manual a breath of fresh air. The book, written by midwife Sister Mary Martin in 1950, champions a no-nonsense philosophy where "children should be a joy, and never a burden." This stood in stark contrast to what Annette describes as today's "martyr mums," who feel compelled to constantly entertain their children and avoid any conflict.

Determined not to raise an "entitled brat," Annette committed to following the book's advice "to a T." Her first step was embracing the concept of "air bathing"—letting her baby nap alone outside. Popular in Scandinavia, the practice involves placing a pram in the fresh air to regulate the child's immune system. While 1950s mothers might have left the pram by the front door, Annette adapted by using her small central London patio.

Sleep Training, Toilet Training and the Power of Boredom

The manual's pragmatic approach extended to sleep. Rejecting the modern ideal of holding a baby for hours, Annette began sleep training from day one using short, reassuring intervals. "Within two weeks, he was napping and sleeping well," she reports. Mothercraft also advocates for early toilet training. Annette started holding her son over the loo after feeds, a method comedian Katherine Ryan also uses, and had him fully trained by 18 months, saving "a fortune in nappies."

When it comes to play and development, the book's ethos is simple: "children ask for love, not riches." Annette actively lets her son experience boredom, believing it stimulates creativity, and provides simple household items for play. She strictly limits screen time, allowing only documentaries or shows like Blue Peter, and condemns the common sight of toddlers glued to tablets in public.

Fitting the Child into Your Life, Not the Other Way Around

Annette applied the book's anti-consumerist principles to her shopping, ignoring lengthy NCT lists and buying mostly second-hand items. Her one splurge was a large pram, as recommended. She also skipped trendy baby classes in favour of the Mothercraft diet: feeding Felix steak, rabbit, liver, and chicken multiple times a day from a young age, with a slice of Madeira cake for pudding.

The core philosophy, she explains, is that the child fits into the family's life. Felix helps set the table and with chores, and Annette encourages his independence by having him order in restaurants. She believes this authoritative parenting style—with clear boundaries and positive reinforcement—fosters discipline and life skills, unlike what she sees as the often ineffectual results of gentle parenting.

While the manual contains some decidedly dated advice for women, Annette was pleased to find a chapter on Fathercraft encouraging shared responsibility. She concludes that by providing a strong moral compass, even if her son veers off course, he will return to values of "morality, sensibility, kindness, and a strong backbone"—a result she feels modern parenting trends often fail to deliver.