As a new year unfolds, a profound psychological shift is taking hold. Instead of looking forward with hope, a growing number of people find themselves trapped in an overwhelming present, unable to envision a stable or brighter tomorrow.

The Paralysing Present: When the Future Disappears

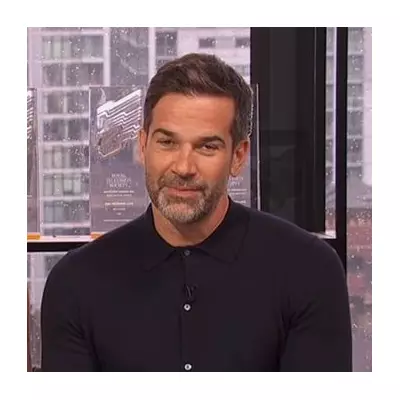

This phenomenon, described by clinical psychologists as losing the future, is becoming widespread. Dr Steve Himmelstein, a New York-based psychologist with nearly five decades of experience, reports that most of his clients have “lost the future.” He notes a stark contrast to periods like the aftermath of 9/11, stating the current climate feels worse.

The daily barrage of negative headlines—from global political instability and economic anxiety to the rising cost of living and severe climate events—leaves people feeling overwhelmed, overstimulated, and bombarded. This constant state of alarm not only heightens anxiety but actively erodes our capacity to plan and commit to long-term goals.

When asked what they are looking forward to, many now have no answer. “They’re not looking forward to things,” Himmelstein explains, describing a consensus among his peers of widespread despair and a lack of personal plans among clients.

The Science of a ‘Polycrisis’ and Our Brain’s Limits

Social scientists define our current era as a polycrisis—a state where multiple, interconnected crises stack and amplify each other’s effects. This creates a state of radical uncertainty, where predicting outcomes feels impossible.

Dr Hal Hershfield, a psychologist at UCLA, explains that our brains are evolutionarily poor at distant future thinking. We don't truly imagine the future; we “remember” it through a process called episodic future thinking. Radical uncertainty disrupts this memory-making, blocking our ability to construct a plausible tomorrow.

Research underscores this: when study participants were reminded of future uncertainty, they generated 25% fewer possible future events and found the task significantly harder. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for envisioning our future selves, is a relatively recent evolutionary addition, leaving us ill-equipped for such pervasive doubt.

Historical Precedents and Paths Forward

We are not the first generation to face this. Anthropologist Dr Daniel Knight of the University of St Andrews studied communities in Greece during the 2008-2010 debt crisis, another polycrisis involving migration, energy, and economy.

He observed two key coping mechanisms: people turned to historical parallels for reassurance, and they recentred on the immediate present, focusing on short-term plans and building “micro-utopias” within their communities through activities like cycling clubs and local support networks.

Knight also points to the 17th century, a period of plague, fire, and religious strife in Europe. That polycrisis ultimately catalysed the Enlightenment, leading to more democratic governance and investment in science. “Our problems may be different now,” Knight says, “but there is still hope. We can make choices and collectively work towards that future.”

How to Reclaim Your Future Vision

Experts advise that while planning feels difficult, it remains crucial. The key is to adapt our approach.

- Focus on Values, Not Fixed Plans: Hershfield suggests anchoring actions in core values, like supporting a child’s education, while being flexible on the exact path.

- Combat Paralysis with Compassion: Avoid regret over past choices and resist the urge to “bury our heads in the sand.” When plans are derailed, it’s acceptable to shift gears.

- Re-focus on the Probable: To counter anxiety, concentrate on events that are most likely to happen, making it easier to connect with your envisioned future self.

- Embrace Community: Following historical examples, engaging with local groups and building small, positive networks can create pockets of stability and purpose.

Ultimately, we are more resilient than we believe. Dr Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard psychology professor, offers a reassuring perspective: “People are not the fragile flowers that a century of psychologists have made us out to be.” He notes that humans are a hardy species, often recovering from tragedy more robustly than they anticipate. The first step forward is recognising that in this polycrisis, if you feel trapped, you are not alone.