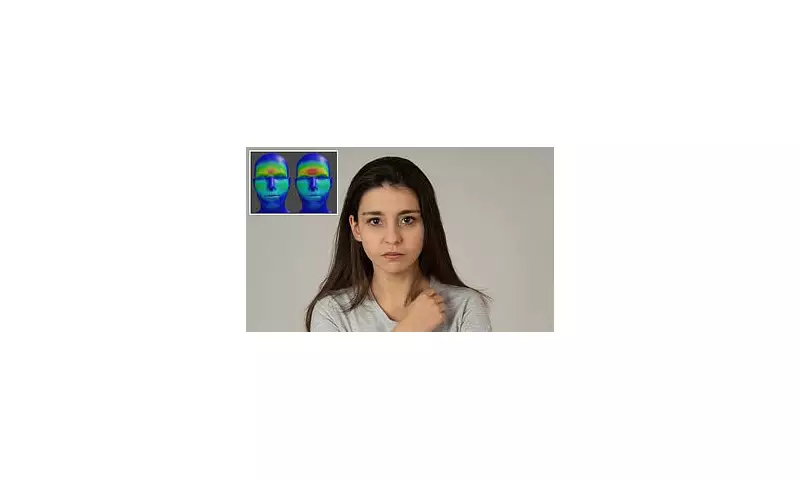

Groundbreaking Study Reveals Autism Creates Distinct Facial Expression 'Language'

Scientists have made a significant breakthrough in understanding how autism affects emotional communication, discovering that autistic individuals express emotions through fundamentally different facial movements compared to neurotypical people. Researchers from the University of Birmingham have identified that these differences create what they describe as a 'different language' of facial expressions, potentially explaining why autistic and non-autistic people sometimes struggle to understand each other's emotional reactions.

Key Differences in Emotional Expression Identified

The comprehensive study, published in the respected journal Autism Research, examined how 25 autistic adults and 26 non-autistic adults expressed three core emotions: anger, happiness, and sadness. Using sophisticated facial tracking technology, researchers recorded approximately 5,000 facial expressions across both groups, revealing consistent patterns of difference.

When expressing anger, autistic participants demonstrated a distinctive pattern of increased mouth movement alongside reduced eyebrow movement compared to their neurotypical peers. This represents a fundamental difference in how this powerful emotion manifests physically between the two groups.

The Complexity of Happiness and Sadness Expressions

The research revealed particularly interesting findings regarding expressions of happiness. Autistic smiles were found to be less exaggerated overall, with participants showing:

- Reduced eye movement during smiling

- Minimal cheek raising

- A smile pattern that didn't fully engage the upper facial regions

This creates what researchers described as a smile that 'doesn't fully reach the upper half of the face', potentially making genuine happiness harder for others to recognize in autistic individuals.

When expressing sadness, autistic participants exhibited a significantly different mouth formation, raising their upper lip more prominently to create a downturned mouth shape that differed markedly from neurotypical expressions of the same emotion.

Understanding the Communication Challenge

Dr Connor Keating, study author now at the University of Oxford, explained the implications of these findings: 'Our research indicates that autistic and non-autistic people differ not only in the appearance of facial expressions, but also in how smoothly these expressions are formed. This creates a two-way communication challenge where both groups may struggle to interpret each other's emotional signals.'

The study also investigated the role of alexithymia - a condition involving difficulty identifying one's own emotions - which was found to be more common among autistic participants. While this condition made distinguishing between angry and happy expressions more challenging, researchers emphasized that autism itself was not the direct cause of alexithymia cases.

Research Methodology and Participant Profile

The carefully designed study involved participants who were closely matched in age, gender, and IQ scores to ensure valid comparisons. All autistic participants had received official clinical diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder, which affects how individuals communicate, interact, and experience the world, typically appearing in early childhood.

Participants completed multiple assessments including:

- Online surveys measuring autism traits and emotional recognition abilities

- Evaluation of simple dot-based animations showing computer-generated facial expressions

- Laboratory sessions where they produced both 'cued' expressions and 'spoken' emotional reactions while saying neutral sentences

Important Limitations and Future Research Directions

Professor Jennifer Cook, the study's senior author, highlighted important considerations: 'What has sometimes been interpreted as difficulties for autistic people might instead reflect a two-way challenge in understanding each other's expressions. Our findings emphasize the need for mutual understanding rather than assuming deficits on one side.'

The researchers acknowledged several limitations to their work:

- The study examined posed expressions rather than spontaneous emotional reactions

- Posed expressions might exaggerate differences between groups

- Researchers didn't measure how these expression differences affect real-time social interactions

- The study didn't investigate how others perceive these expression differences during actual conversations

Broader Context and Related Findings

Autism spectrum disorder affects approximately one in 31 children in the United States according to recent CDC data, representing more than three percent of the childhood population. The condition varies widely in symptoms and severity, earning its description as a 'spectrum' disorder.

This facial expression research builds on other recent discoveries about autism, including studies identifying distinct walking patterns sometimes described as a 'duck butt' posture in autistic children, who often exhibit a more forward-tilted pelvis while walking compared to neurotypical peers.

The Birmingham team's findings suggest that autistic individuals may rely more heavily on general intelligence and cognitive processing to recognize emotions in others, since their own facial expression patterns don't match neurotypical norms. This was particularly evident in tests where autistic participants demonstrated strong abilities in recognizing emotions in computer-generated images while still struggling with interpreting real human expressions.

This groundbreaking research opens new avenues for understanding neurodiversity and developing better communication strategies between autistic and non-autistic individuals, emphasizing that differences in expression represent alternative communication styles rather than deficits.