Europe's Populist Resurgence Sends Warning Signal

While American Democrats bask in the afterglow of recent electoral successes, a cautionary tale is unfolding across central Europe that should temper any premature celebrations. The remarkable resilience of right-wing populist movements in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland demonstrates that electoral defeats often prove temporary rather than fatal to such political forces.

The Comeback Kings of Central Europe

In the Czech Republic, wealthy oligarch Andrej Babiš stands on the verge of an extraordinary political return. His ANO party emerged as the largest bloc in last month's parliamentary election, positioning him to form a coalition government with far-right anti-immigrant parties and previously fringe anti-environmental groups. This represents a stunning reversal for Babiš, who lost power four years ago amid conflict-of-interest scandals and mass protests reminiscent of recent demonstrations in the United States.

Babiš's comeback mirrors that of his Slovak counterpart Robert Fico, who returned as prime minister in 2023 after his Smer party won elections five years following his resignation. Fico's political resurrection came despite his government's collapse after popular street protests triggered by the murder of an investigative journalist. The former socialist, who spoke at this year's CPAC gathering in Maryland, has dramatically shifted Slovakia's foreign policy, abandoning support for Ukraine in favour of closer ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Meanwhile, in Poland, the right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS) demonstrated its enduring appeal when its candidate Karol Nawrocki narrowly defeated Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski in last June's presidential election. This victory came less than two years after PiS was ousted from parliamentary power by a coalition led by the Civic Platform party.

Parallels with American Politics

Czech commentator Albin Sybera identifies several factors driving populist resilience that should concern American observers. "The resilience feeds on similar ingredients and polarization is one common theme," he notes. Another critical element is "the failure of liberal or centrist parties to find a lasting solution to economic discontent" stemming from rapidly changing economic landscapes that have seen traditional manufacturing jobs disappear.

Steven Levitsky, Harvard University politics professor and co-author of How Democracies Die, observes that populist movements benefit from possessing what mainstream parties often lack: "The only one with any real ideology, any real passion, any real project, is the far right. The far-left, center-left, liberal-center, Christian Democrats – none of them have a real project."

The political landscape in most western democracies has fundamentally shifted, with traditional left-right arguments about government spending and taxation giving way to conflicts between urban cosmopolitan secularism and rural traditional nationalism. "Politics in most western democracies is now primarily cleaved along what you can call cosmopolitan versus populist lines," explains Levitsky.

Democratic Ideals Under Pressure

Eric Rubin, a former US ambassador and ex-president of the American Foreign Service Association, offers a sobering perspective on democratic resilience. "The assumption that people, given a choice, will prefer democracy, they want to elect their own leaders, they want freedom of speech and all the other freedoms – as a default, that's probably true but there are trade-offs," he suggests.

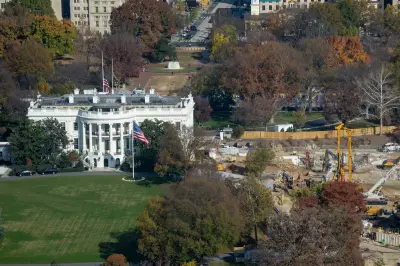

Rubin's warning carries particular weight given Donald Trump's open admiration for Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's illiberal governance model. Orbán, who visited Trump at the White House recently, has won four consecutive elections amid allegations of gerrymandering and institutional takeover. Though polls currently show his Fidesz party trailing opposition ahead of next spring's election, his longevity demonstrates populism's staying power.

The central European experience suggests that even the most optimistic Democratic scenario – regaining control of the House of Representatives in next year's midterms and winning the White House in 2028 – might not permanently break the feverish intensity of Trump's Maga movement. As these European examples demonstrate, defeated populists possess remarkable capacity for electoral resurrection, finding ways to exploit economic anxieties and cultural grievances that centrist parties struggle to address effectively.