A senior human rights researcher has issued a stark warning, drawing direct parallels between the United Kingdom's recent legislative crackdown on protests and the gradual erosion of democratic freedoms witnessed in Viktor Orbán's Hungary.

A Chilling Sense of Déjà Vu

Lydia Gall, a senior Europe researcher at Human Rights Watch, states that watching developments in the UK evokes an uneasy sense of recognition. Having witnessed Hungary's democratic backsliding first-hand, she notes it began not with dramatic upheavals but with incremental legal changes that steadily narrowed the space for dissent.

In the UK, this shift is embodied in two key pieces of legislation: the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 and the Public Order Act 2023. These laws grant police extensive powers to restrict demonstrations, criminalise previously peaceful tactics, and make arrests on vague grounds of potentially causing 'serious disruption' or 'unease'.

The Growing Chilling Effect on Dissent

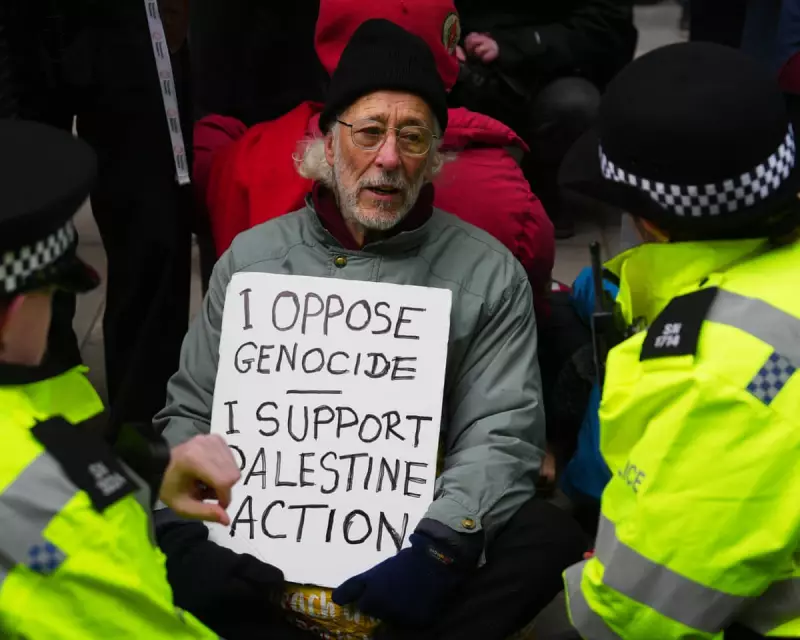

The practical impact has been significant. Hundreds of arrests have followed, targeting actions such as slow marching, linking arms, or simply carrying protest equipment. Many face prosecution, with courts imposing fines and, in some instances, lengthy prison sentences for peaceful protest activities.

While officials frame the measures as balancing acts for public order, Gall argues the balance has tipped decisively towards control. Protesters and legal observers report confusion over what is lawful, inconsistent police actions, and arbitrary arrests—even when demonstrations are pre-coordinated with authorities.

This creates a climate of uncertainty and hesitation that actively discourages people from exercising their right to assemble and speak out.

Parallels with Authoritarian Consolidation

The pattern, Gall asserts, is alarmingly familiar. In Hungary, authoritarianism took root through the steady consolidation of state power under the guise of preserving 'order' and 'safety'. Independent institutions, from the judiciary to media and academia, were systematically undermined.

The danger lies in how quickly laws written in neutral language can become instruments of repression when legal safeguards erode. This risk was highlighted in a UK High Court ruling last year, which found that then Home Secretary Suella Braverman acted unlawfully by attempting to lower the protest threshold from 'serious' to 'more than minor' disruption.

Gall notes the Labour government's subsequent decision to defend these unlawful regulations in court, rather than repeal them, as a troubling signal that the instinct to control dissent transcends party lines.

A Warning and a Call to Action

The expansion of state power has extended beyond street protests. The proscription of the group Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation marked an alarming phase, conflating civil disobedience with extremism—a tactic criticised by UN experts for blurring the line between legitimate activism and terrorism.

"The UK is not Hungary, but the direction it is taking is alarmingly familiar," Gall writes. She warns that today's 'anti-disruption' powers could tomorrow be used to suppress strikes, silence journalists, or target minority communities.

The lesson from Hungary is how rapidly governments can manipulate legal frameworks to serve political ends, and how difficult it is to reverse that process. Gall calls on UK authorities to change course by:

- Repealing or amending the most repressive elements of recent protest laws.

- Ending the use of 'suspicion-less' stop and search powers.

- Committing to full transparency and accountability in police operations.

Ultimately, she urges a fundamental recognition: dissent, however disruptive, is not a threat to democracy but its essential safeguard. Freedom of assembly, she concludes, is a right that protects citizens from their governments, not a privilege governments grant.