Royal Silence: How a Black Abolitionist's Plea to End Slavery Was Ignored

In the autumn of 1786, a remarkable parcel arrived at Carlton House, the London residence of George, Prince of Wales. It was sent by Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, a free Black man living in the city, one of approximately 4,000 people of African descent in London at that time. Inside were pamphlets detailing the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and the brutal treatment of enslaved individuals in Britain's Caribbean colonies. The accompanying letter, signed under Cugoano's alias "John Stuart," implored the heir to the British throne to read the enclosed "little tracts" and to "consider the case of the poor Africans who are most barbarously captured and unlawfully carried away from their own country."

A Personal Appeal to the Monarchy

Cugoano, who was employed as a domestic servant by the fashionable painters Maria and Richard Cosway, lived just two blocks from Carlton House. Richard Cosway had recently been appointed principal painter to the Prince of Wales, and their home at Schomberg House on Pall Mall became a hub for artists, aristocrats, and politicians. Through this position, Cugoano gained rare, direct access to Britain's elite and the royal family, which he used to full advantage in his abolitionist efforts.

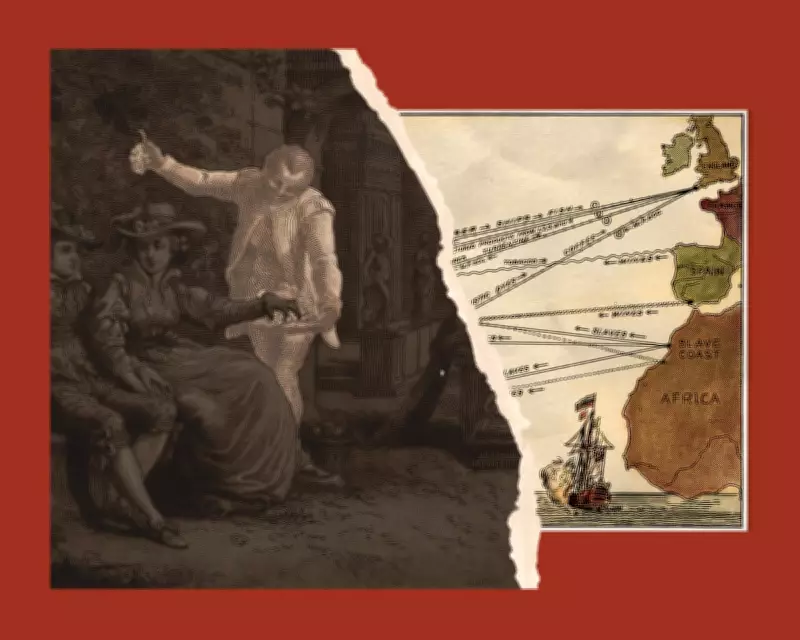

Born around 1757 in a Fante village in what is now Ghana, Cugoano's childhood was shattered when slave traders raided his community. At the age of 13, he was kidnapped, forced into chains, and transported across the Atlantic to Grenada, where he endured plantation labour. After nearly two years, he was brought to England in late 1772, shortly after Lord Mansfield's ruling in the Somerset case, which many misinterpreted as granting freedom upon touching English soil. Cugoano soon claimed his liberty, though freedom in London remained precarious for formerly enslaved people.

The Strategic Campaign for Abolition

Over the next decade, Cugoano learned to read and write, became a devout Anglican, and immersed himself in London's free Black community. By the mid-1780s, he had joined the Sons of Africa, a group of Black activists including former enslaved men and sailors. Together, they engaged in acts of resistance, such as lobbying MPs and intervening to prevent the illegal seizure of free Black individuals. One notable success was the rescue of Harry Demaine, who was nearly re-enslaved and shipped to the Caribbean.

Cugoano understood that abolishing the slave trade required more than grassroots efforts; it needed the support or acquiescence of the monarchy. From his vantage point at Schomberg House, he observed the Prince of Wales's vanity and obsession with legacy, tailoring his appeal accordingly. In his letter, Cugoano promised that if the prince used his future power to end the "iniquitous traffic of buying and selling men," his name would "resound with applause from shore to shore" and be held "in the highest esteem throughout the annals of time."

A Direct Confrontation with Royal Power

The following year, Cugoano sent the prince a copy of his book, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, the first anti-slavery treatise written by a formerly enslaved African in Britain. He reminded the prince that enslaved Africans had no formal representatives and their only hope was to "lay our case at the feet of your Highness." While the Prince of Wales kept the book in the royal collection, he took no further action.

Cugoano also sent his book to King George III, appealing to Christian duty and moral responsibility. However, his work did not flatter the monarchy; it indicted it. He argued that European kings had sanctioned and profited from the slave trade for centuries, with the transatlantic trade formally established by royal authority under Charles II. Cugoano insisted that claiming royal innocence was a fiction, as the monarchy normalised and legitimised slavery, setting a corrupt example for the nation.

The Legacy of Silence

Cugoano's book initially attracted little attention, but by 1791, an abridged edition gained influential subscribers, and the abolitionist movement he helped build gathered momentum. He vanished from historical records soon after, but his book remains in royal hands, a testament to his direct confrontation with the slave system. The monarchy had been offered an opportunity for moral leadership but declined, a silence that would echo for generations.

This story underscores the complex links between the British royal family and slavery, revealing how appeals for justice were met with indifference at the highest levels of power.