Holocaust survivor's daughter fulfils vow to bring lost art to UK

In a poignant culmination of decades of perseverance, Judy King has honoured a deathbed promise to her mother by securing the safe arrival of hundreds of precious artworks in the United Kingdom. The collection, created by the Jewish artist and poet Peter Kien in the Theresienstadt ghetto, has found a new permanent home at the Wiener Holocaust Library in central London.

A legacy saved from tyranny

The remarkable journey of these 681 drawings, love letters, poems, and manuscripts began in German-occupied Czechoslovakia between 1941 and 1944. On the eve of his deportation to Auschwitz, where he was murdered at age 25, Kien entrusted a small caramel-brown suitcase containing his life's work to his lover, Helga Wolfenstein. Wolfenstein, aided by her mother who served as matron of the ghetto's infectious diseases ward, hid the suitcase, correctly gambling that Nazi forces would avoid the health risks of entering such a place.

Following the liberation of Theresienstadt in 1945, Wolfenstein fled Prague for Libya and later England, leaving the suitcase with her aunt in Czechoslovakia. She feared, rightly, that the new communist regime would confiscate the artworks if she attempted to remove them. This foresight proved tragically accurate when, in the 1970s, a communist informant discovered the suitcase's contents, leading authorities to seize it under threat of stripping Wolfenstein's pension.

Decades of determined struggle

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989 ended communist rule, the works were transferred to the Terezín Memorial, a museum dedicated to commemorating ghetto victims. While the museum briefly exhibited the art with Wolfenstein's permission, it subsequently refused her repeated requests for their return, citing a lack of formal provenance—a cruel irony given the chaotic circumstances of their seizure.

Wolfenstein, who spoke seven languages, spent 33 years writing to institutions worldwide in a passionate but often fruitless campaign to recover what she called suitcase #681. Her daughter, Judy King, recalls her mother's near-obsessive dedication, albeit sometimes hindered by her blunt correspondence style. "She would begin letters to the Terezín people with 'You thieves' instead of 'Dear Sir or Madam'," King noted wryly.

A promise fulfilled against the odds

Upon her mother's death in 2003 at age 81, King made a solemn vow: "I will finish your work." This commitment launched her own lengthy battle, involving diplomatic efforts, legal hurdles, and sheer persistence. A breakthrough came in 2017 when King and her cousin Peter visited the Terezín Memorial, finding officials more willing to negotiate than they had been with her mother.

However, significant obstacles remained. The artworks were classified as national treasures, prompting reluctance from Czech authorities to part with them. King, a US resident born in America, leveraged support from American officials and the advocacy of German writer Jürgen Serke to maintain pressure. Critical to the resolution was a handwritten, notarised document from Wolfenstein, bequeathing the suitcase and its contents to King—a testament to her mother's paranoia as a Holocaust survivor, which ultimately satisfied provenance requirements after initial customs objections.

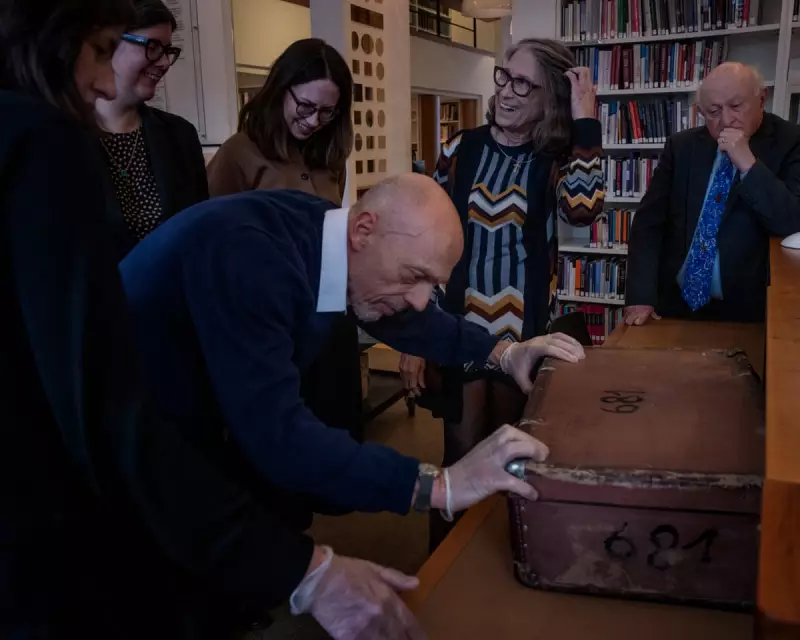

The final transfer was fraught with tension, nearly derailed by a Czech customs guard's last-minute demand for a court-appointed document and adverse British weather that delayed the suitcase's blustery landing at Heathrow. Yet, through coordinated efforts with shippers in London and Prague, the artworks finally arrived last Thursday.

A new home for historical testimony

Now housed at the Wiener Holocaust Library, the collection joins nearly a hundred other Kien works smuggled out by King's cousin during the communist era. Howard Falksohn, the library's senior archivist, expressed profound gratitude for the donation, highlighting its significance ahead of International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The artworks offer a haunting visual record of everyday life in the Theresienstadt ghetto, preserving Kien's legacy and Wolfenstein's courageous safeguarding.

Reflecting on the achievement, King believes her mother—an Anglophile who worked for the Post Office in London and became a British citizen—would have been thrilled to see the treasures donated to a UK institution. This story stands as a powerful testament to familial loyalty, the enduring impact of art, and the relentless pursuit of justice across generations.