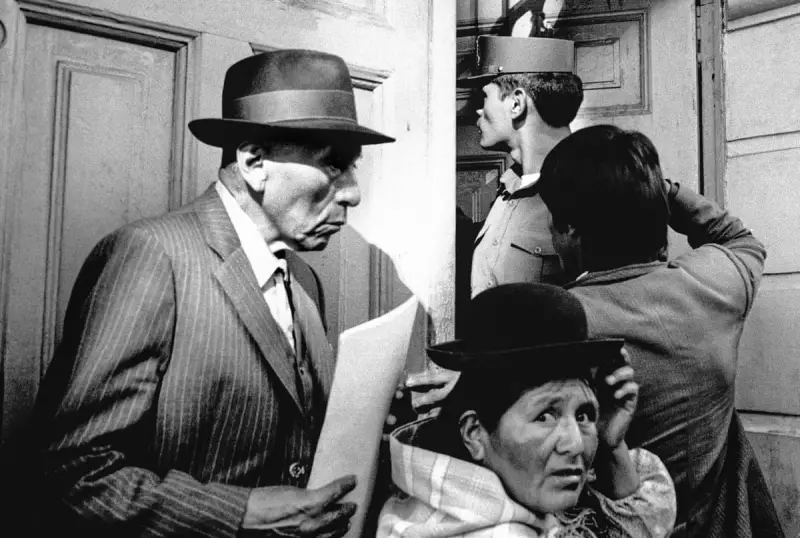

In 1993, photographer Rod Morris found himself in the high-altitude city of La Paz, Bolivia, during a period of intense political apprehension. The election of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada as president was looming, and the atmosphere across the capital was thick with tension. Soldiers and police officers were a common sight on the streets, while rumours circulated that any unregistered land might be sequestered by the incoming government.

A Fateful Commission and a Captured Moment

Morris had arrived in South America after winning a travel photography competition, which granted him a return ticket to anywhere in the world. He chose Chile, spending three months there before boarding a train to the Bolivian Altiplano. He was working under an open-ended commission for the Financial Times to provide photographs from financial districts in South American cities. While his primary aim was to wander and capture compelling scenes, he made a point of visiting La Paz's financial and government quarters.

It was there that he encountered a significant queue of people, clutching papers and waiting with palpable anxiety. "There was no way to be discreet when I took it," Morris recalls. "My camera was quite loud and you can see one of the people looking right at me." He sensed the urgency of the situation, gathering that claims had to be filed before an imminent deadline, though he wasn't entirely certain of the specifics. The composition itself felt charged; figures formed a chain leading towards an open doorway guarded by a soldier, creating a visual narrative of tension and bureaucratic procedure.

A Violent Aftermath and a Warning

Shortly after taking the photograph, Morris was approached by plainclothes police officers. They bundled him into the back of a car and drove him to a local station for prolonged questioning about his presence and activities. Despite explaining he was a tourist taking personal photographs, the officers attempted to confiscate his film. Morris managed to divert them by handing over some unexposed rolls.

The encounter turned violent upon his departure. "On the way out, I had to walk down a line of police who took turns to punch and kick me all the way to the door," he states. This physical assault served as a stark warning, accompanied by a threat that he would be followed and watched. Heeding this, Morris did not linger in the area.

The Image's Legacy in Still Films

This particular photograph, along with many others from that time, was not published initially. It now forms a crucial part of Morris's series titled Still Films, which explores the intersection between his photojournalism and film-making backgrounds. The series delves into the interplay between cinema and photography, focusing on still images that evoke narratives extending beyond the frame.

Reflecting on the image, Morris notes its "filmlike quality" and the ambiguity within its tense composition. "I think the best photographs provide more questions than answers," he muses, emphasising his preference for images that are not too rigid or immediate, but instead carry the sense of excitement and wonder he felt in the moment.

Philosophy and Approach

Morris has always been drawn to black and white, filmic imagery, and scenes that appear almost staged. He is reluctant to enter a situation as an outsider attempting to dictate a story. "I arrived in Bolivia without foreknowledge or judgment," he explains, suggesting that the specific political context is somewhat secondary to the powerful, human moment captured. The image stands as a testament to a tense period in Bolivian history, a photographer's instinct, and the sometimes brutal consequences of documenting truth.