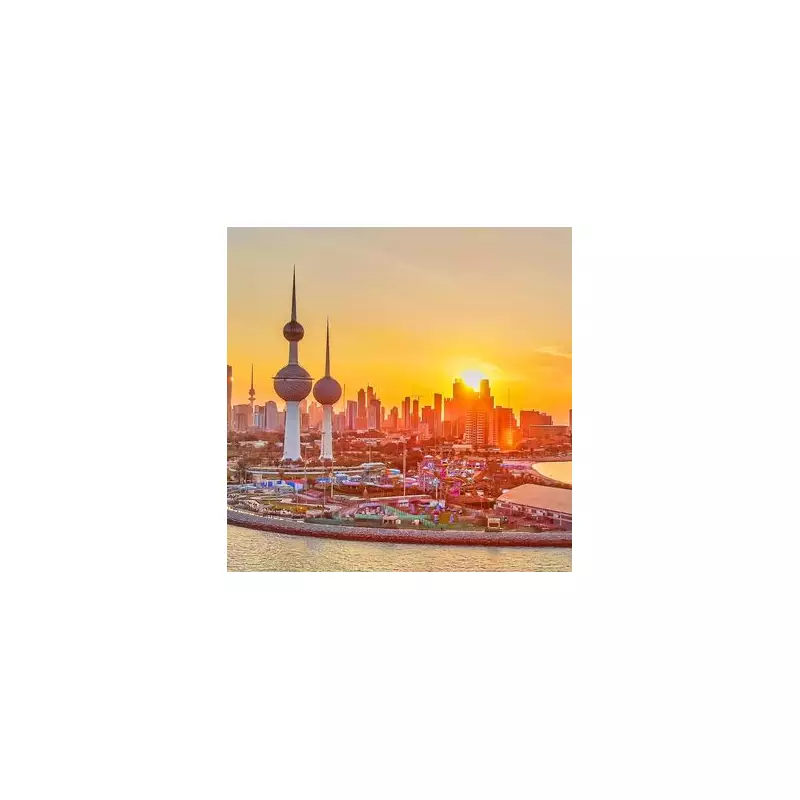

Kuwait City, often described as the world's hottest city, is experiencing scenes of an almost biblical nature, with reports of birds dropping dead from the sky and marine life perishing in boiling waters.

A City Transformed by Extreme Heat

Once celebrated as the 'Marseilles of the Gulf' for its bustling ports and vibrant coastal life, Kuwait City's character has been fundamentally altered by relentless and soaring temperatures. Where European heatwaves might cause discomfort, the conditions here pose a genuine and lethal threat to both humans and wildlife.

The severity of the heat is not anecdotal; it is starkly recorded in scientific data. On 21 July 2016, the Mitribah weather station in northern Kuwait registered a staggering 54°C (129°F), marking the third-highest temperature ever verified on Earth. Forecasts are grim, predicting a further rise of 5.5°C before the end of the century.

Apocalyptic Scenes and Human Adaptation

The consequences of this extreme heat are visceral and disturbing. There are documented instances of seahorses being cooked alive in the bay and mass bird fatalities. Even resilient urban pigeons are forced to seek constant shelter. In 2021, the city endured more than 19 days where the mercury soared above 50°C, a figure expected to be surpassed in the coming years.

For residents, daily life has been forced to adapt radically. The government has taken the extraordinary step of permitting night-time funerals to avoid the deadly daytime heat. Those with the means retreat into a perpetually air-conditioned existence, moving between homes, offices, and shopping centres. A 2020 study revealed that a massive 67% of household electricity use is dedicated solely to powering air conditioning units.

This has spurred the development of climate-controlled infrastructure, such as indoor shopping streets styled like European avenues, offering a sanctuary from the hostile environment outside.

A Population at Risk and a Lagging Response

Kuwait's streets remain busy, largely due to its demographic makeup. Migrant workers, constituting around 70% of the population and primarily from South and Southeast Asia, fill the pavements and buses, often labouring outdoors in construction and domestic services under the controversial kafala system.

Latest research underscores their acute vulnerability. Studies suggest that without decisive climate action, heat-related deaths could increase by up to 11.7% in Kuwait by 2100, potentially reaching 15% among the non-Kuwaiti population. Despite these warnings, Kuwait's climate commitments remain modest, with a goal to cut emissions by just 7.4% by 2035 set at COP26.

Compounding the issue, the state subsidises most electricity and water costs, including for energy-intensive desalination, removing any financial incentive for conservation. Energy use is projected to triple by 2030.

Environmental expert Salman Zafar warns of a dire future, citing risks from floods and droughts to biodiversity loss and disease outbreaks. In Kuwait City, the abstract threat of global warming is a concrete, searing reality, offering a stark preview of what may await other regions if climate change continues unabated.