Sydney's Beach Crisis: The 16-Month Battle to Expose the Fatberg Truth

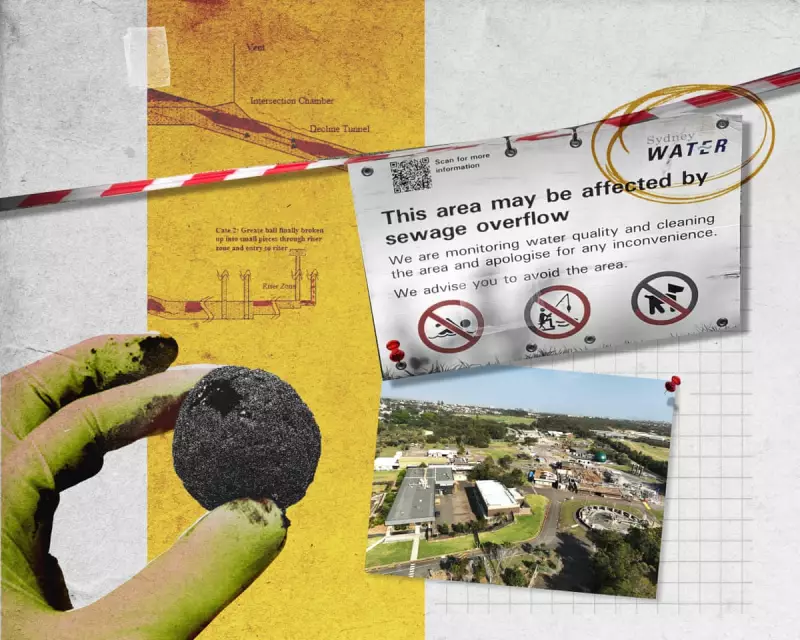

In a startling environmental scandal, a colossal fatberg lurking within Sydney Water's Malabar sewage treatment plant has been identified as the primary culprit behind the notorious 'poo balls' that forced the closure of numerous Sydney beaches. This revelation culminates a protracted 16-month struggle for transparency, during which authorities appeared reluctant to disclose the full extent of the problem to the public.

The Initial Outbreak and Official Silence

Following heavy rainfall in Sydney last week, fresh debris balls, infamously dubbed 'poo balls', washed ashore at Malabar beach, situated perilously close to the problematic Malabar sewage facility. While warning signs were promptly erected advising against swimming or touching the mysterious objects, a broader public alert was conspicuously absent. Neither Sydney Water, the Environment Protection Authority (EPA), nor the state government issued any comprehensive warnings, leaving the community largely in the dark.

Since October 2024, when these balls first emerged on Coogee beach, Sydney Water has been notably slow to accept responsibility for the pollution that led to the shutdown of over a dozen coastal areas until January 2025. Concurrently, questions have been raised regarding the NSW EPA's willingness to share critical information openly with citizens.

A Pattern of Denial and Delayed Disclosure

Initially, the debris was misleadingly labelled as 'mystery tar balls'. By mid-October 2024, Guardian Australia reported that scientists were probing potential links to sewage outfalls, a theory that Sydney Water vehemently contested. The corporation's media team even attempted to have references to it removed from related news stories, while other outlets continued to propagate the tar ball narrative.

Internal understanding suggests the EPA was aware as early as 25 October 2024 that the pollutant material was consistent with human waste. However, the definitive announcement that the balls were mini fatbergs containing human faeces was strategically made late on 6 November 2024, coinciding with the US election news cycle. At that juncture, the source remained officially 'unknown', with the EPA citing the complex composition as a barrier to pinpointing origins.

A Sydney Water spokesperson maintained that their wastewater plants were operating normally, suggesting the balls might have merely absorbed pre-existing wastewater during formation. This stance persisted into early April 2025, when the EPA finally conceded the likely origin was Sydney Water's land-based sewage network, yet officials continued to downplay the issue, emphasising regulatory compliance.

The Freedom of Information Breakthrough

It was only after a rigorous five-month freedom of information campaign by Guardian Australia that the truth began to surface in October 2025. The investigation confirmed the debris balls were emanating from the deepwater ocean outfalls, as multiple experts had long suspected. Even then, during a briefing on a redacted report, Sydney Water and the EPA withheld the specific identification of the Malabar outfall as the precise source, revealing it only after media publication.

An oceanographic report commissioned by Sydney Water indicated the corporation could have known by 3 February 2025 that its outfalls were the likely source, based on a preliminary draft. The final report, completed in late May, underscored the severity of the issue. By August 2025, a separate report obtained by Guardian Australia pinpointed a fatberg the size of four buses in an inaccessible dead zone at the Malabar plant, describing it as the probable birthplace of the poo balls.

An Intractable Engineering and Political Quandary

The report highlights a dire situation: fats, oils, and grease have accumulated in an area between the Malabar bulkhead door and the decline tunnel, rendering clearance nearly impossible. Remedying this would necessitate shutting down the 2.3km offshore outfall for maintenance, diverting sewage to cliff face discharge—a move that would close Sydney's beaches for months and is deemed unacceptable.

In response to mounting scrutiny, Sydney Water and Water Minister Rose Jackson engaged in pre-emptive spin, re-announcing a $3bn investment in the Malabar system. However, this funding was not new; it was part of a pre-existing $34bn capital plan announced in September 2024, with no allocation for enhancing sewage treatment at coastal plants. Instead, it aims to reduce the load heading to these facilities.

Financial constraints further complicate matters. Sydney Water's proposal for a 53% bill increase over five years was curtailed by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (Ipart) to a maximum of 13.5% in the first year and 5% annually thereafter, including inflation. The 2025-26 NSW budget included no capital allocations for Sydney Water, pending Ipart's decision, casting doubt on the feasibility of the massive works plan.

Additionally, Minister Jackson's request for government funding to expand Sydney's desalination plant was reportedly rejected by the NSW treasurer, despite its critical role in future water security. The deepwater outfalls, originally chosen as a cost-effective solution in the 1990s, now present a formidable challenge requiring significant political will and advanced engineering to resolve.

This saga underscores a broader issue of environmental accountability and public transparency, as Sydney grapples with the lingering impacts of pollution on its iconic beaches.