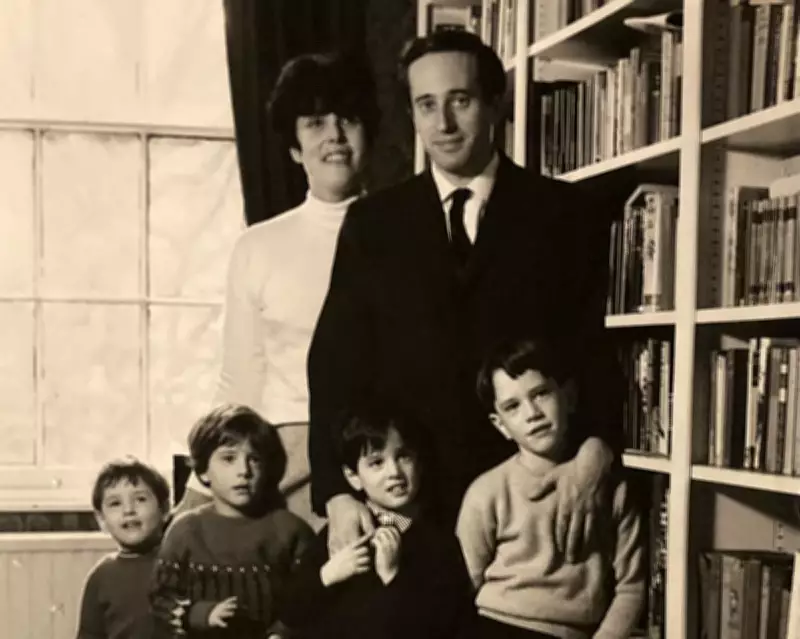

In the mid-1960s, the Glanville family captured a moment of togetherness, a stark contrast to the challenges that would later unfold as dementia and Parkinson's disease took hold. For Jo Glanville, a journalist and radio producer, the key to breaking through the fog of her parents' conditions was an unexpected tool: reading aloud. This simple act led to a profound discovery about the resilience of the human mind, even in the face of degenerative illnesses.

The Radioactive Damage of Dementia Care

Novelist Ian McEwan has spoken candidly about the distressing nature of dementia, describing his mother as "alive and dead all at once" and highlighting the "radioactive damage" it inflicts on caregivers. Jo Glanville's personal experience echoes this sentiment, yet she offers a different perspective. Her mother, Pamela, a journalist, passed away from vascular dementia a decade ago, while her father, Brian Glanville, a renowned football journalist and novelist, died last year after a five-year battle with Parkinson's and a milder form of dementia.

While McEwan's metaphor of "radioactive damage" vividly captures the emotional toll, Glanville challenges the notion that individuals in advanced stages are essentially "dead." She poses a critical question: How can we truly know what is happening within someone else's brain? This uncertainty became the foundation for her journey of connection.

A Revelation Through Reading

The great revelation for Glanville came through the simple act of reading to her parents. She discovered that, in many respects, their cognitive abilities remained remarkably intact. Both Pamela and Brian continued to enjoy being read to until the very end of their lives, responding positively to stories, poems, and novels throughout their illnesses.

They retained their capacity to comprehend narratives and follow complex plots, as well as their understanding of obscure vocabulary. One memorable instance involved reading Arthur Koestler's memoirs to her father. Brian noticed that Glanville wasn't reading them in chronological order—a detail she hadn't even realised herself, showcasing his sharp, unimpaired mind.

The Silent Struggle and the Bridge of Connection

However, neither parent could verbally express their desire to be read to. This need was discovered purely by accident. Her father would spend days sitting silently, unable to move or initiate activities without assistance from his dedicated care worker, Molly. To an outsider, he might have appeared vacant or "dead" to the world, but Glanville observed that Parkinson's and dementia had stolen his ability to start conversations or articulate desires.

She describes it as if a crucial "motor" in the brain, responsible for connecting with the external world, had been destroyed by illness. It was only through persistent efforts—asking questions, encouraging communication, and, most importantly, reading aloud—that this connection could be re-established. Reading became a vital bridge, revealing that sophisticated cognitive functions were entirely unaffected by dementia.

Glanville witnessed a similar process with her mother. At one point, Pamela seemed to lose the ability to follow stories, but when Glanville began reading Doris Lessing's memoir about cats, her mother, a lifelong cat lover, became fully engaged once more.

Lessons for Caregivers and Society

From these experiences, Glanville learned a crucial lesson: never assume that silence or lack of communication in someone with a degenerative illness equates to an inability to understand or engage. Caregivers must actively seek ways to make connections, as the mind may be more vibrant than outward appearances suggest.

Her story is not an isolated incident. Case studies from the charity The Reader demonstrate that reading aloud can have dramatic effects on individuals with dementia, often triggering fluency and communication in response to literature. An evaluation by Philip Davis at the University of Liverpool found that such reading sessions significantly reduced symptom severity and enhanced overall wellbeing.

A Stand Against Assisted Dying

Glanville acknowledges that there may come a point, particularly with severe conditions like Alzheimer's, where connection becomes impossible. However, she firmly believes that "death" only occurs when physical functions cease. People with dementia require strong advocates, and she opposes the extension of assisted dying to this group, arguing that pleasures and connections can still be found even as the world dims.

In conclusion, Jo Glanville's heartfelt account underscores the transformative power of reading aloud in dementia care. It challenges societal perceptions, advocates for continued engagement, and highlights the enduring humanity within those affected by these devastating illnesses.