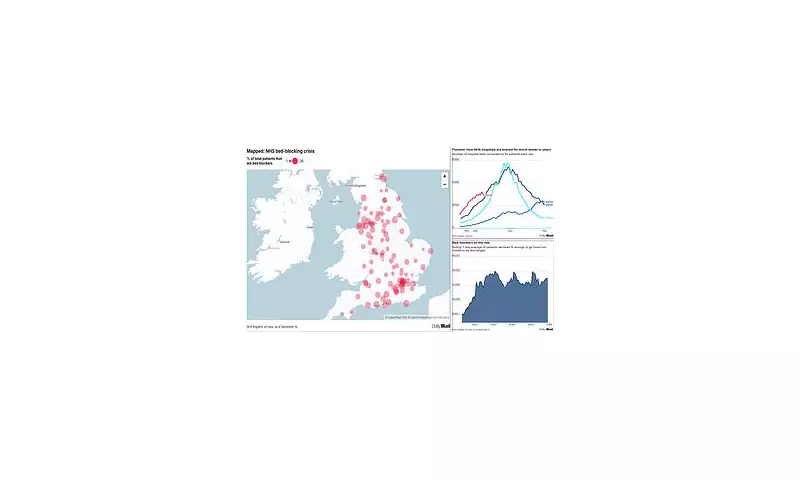

Alarm is spreading across the National Health Service as a severe 'bed-blocking' crisis threatens to overwhelm hospitals during their busiest period. With the NHS bracing for a potential winter meltdown, an investigation has found that close to 13,000 beds are currently occupied by patients who are medically fit to be sent home.

Scale of the Discharge Delays

The situation is most acute in some of England's major hospital trusts, where as many as one in four beds are unavailable for new admissions due to delayed discharges. As of December 14th, official NHS figures show 12,386 beds were taken up by patients declared fit for discharge. This marks a stark increase from pre-pandemic levels, which typically hovered around 5,000.

Four trusts are experiencing particularly high rates: Epsom and St Helier (24.2%), Warrington and Halton (23.3%), Morecambe Bay (23.3%), and East Sussex (23.1%). In practical terms, this means 144 out of 596 beds are blocked in Epsom and St Helier, 130 out of 557 in Warrington, 137 out of 589 in Morecambe Bay, and 160 out of 692 in East Sussex.

A Perfect Storm of Winter Pressures

This bed-blocking crisis is colliding with the NHS's most challenging season. Hospitals are grappling with the worst flu outbreak on record, with more than 3,100 patients currently hospitalised with the virus. Regional data shows sharp increases, including a 33% rise in flu hospitalisations in south-east England.

Consequently, A&E units are becoming dangerously clogged. Patients are facing waits of days for a bed, often receiving treatment in corridors—a practice known as 'corridor care'. Ambulance crews are also experiencing significant delays, unable to hand over patients to emergency teams and therefore unable to respond to new, life-threatening 999 calls.

Compounding the problem is ongoing industrial action. Thousands of resident doctors—formerly junior doctors—began a five-day walkout on Wednesday in pursuit of a 26% pay rise, which will not conclude until 7am on Monday. This strike, the 14th since March 2023, coincides with staff holidays and the festive period, stretching remaining staff dangerously thin and potentially hindering the discharge process for patients who are ready to leave.

Root Causes and Human Impact

The majority of patients stuck in hospital are elderly, with a critical lack of space in social care identified as the primary reason they cannot be discharged. Issues include insufficient home care packages, a shortage of care home beds, and high vacancy rates in the social care sector.

Dr Ian Higginson, President of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, warned of the dangers. "Extended inpatient bed stays can lead to deconditioning and increase the risk of catching a hospital-born infectious disease," he stated. He emphasised that the scale of the problem has forced the use of overflow areas, exposing patients to greater risk.

Caroline Abrahams, Charity Director at Age UK, highlighted the systemic failure. "The NHS and social care are two sides of the same coin and trying to improve one while leaving the other largely untouched, and struggling, is a triumph of hope over experience," she said. She pointed to postponed social care reform as a key factor in the current crisis.

The financial toll is immense, with internal NHS estimates suggesting delayed discharges cost the service approximately £2.6 billion annually. Each five-day doctors' strike carries an additional cost of around £300 million in lost activity and overtime.

In a bid to mitigate the festive period crisis, NHS bosses have been instructed to make a "huge effort" to discharge as many patients as possible to get people home for Christmas. However, with the system under unprecedented strain from flu, strikes, and systemic social care shortages, the path to relieving the pressure remains fraught with challenge.