A microscopic mite is causing a major public health concern across the United Kingdom, with cases of scabies soaring and leaving thousands in distress. New data reveals a 44% increase in diagnoses between 2023 and 2024, turning a once-stable condition into a growing epidemic.

The Personal Hell of a Scabies Infestation

For Louise, a 44-year-old mother from south-west England, the battle was all-consuming. After telltale spots appeared on her and her children in September, her life became a relentless cycle of treatment and decontamination. "It was hell," she confesses. "My mental health was in the pan, the scratching, the itching drives you insane... I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy."

Her family's extreme measures included washing laundry after every use, steaming soft furnishings, and eventually a "nuclear option" – evacuating their home for a week to a rented caravan after multiple treatment rounds failed. Her story is echoed on social media by desperate individuals reporting sleepless nights, skin that feels "on fire," and a profound sense of isolation.

Understanding the Scabies Surge: Data and Causes

Official figures paint a stark picture. A 2024 report from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) analysed cases presenting at sexual health services in England, finding 4,872 diagnoses in 2024, up from 3,393 the previous year. This contrasts sharply with the pre-pandemic average of around 1,500 annual cases.

Similarly, surveillance by the Royal College of General Practitioners shows cases remain stubbornly above the five-year average, peaking at almost double in the final four months of 2023, with the north of England particularly affected.

Experts are grappling with the reasons behind the surge. Dr Donald Grant, a GP and senior clinician at The Independent Pharmacy, points to a "ping-pong" effect of reinfestation within households, exacerbated by post-pandemic mixing and past treatment shortages. Professor Michael Marks of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine adds that outbreaks in crowded settings like university halls, combined with delays in accessing care and inadequate contact tracing, are likely contributors.

The Challenge of Treatment and Stigma

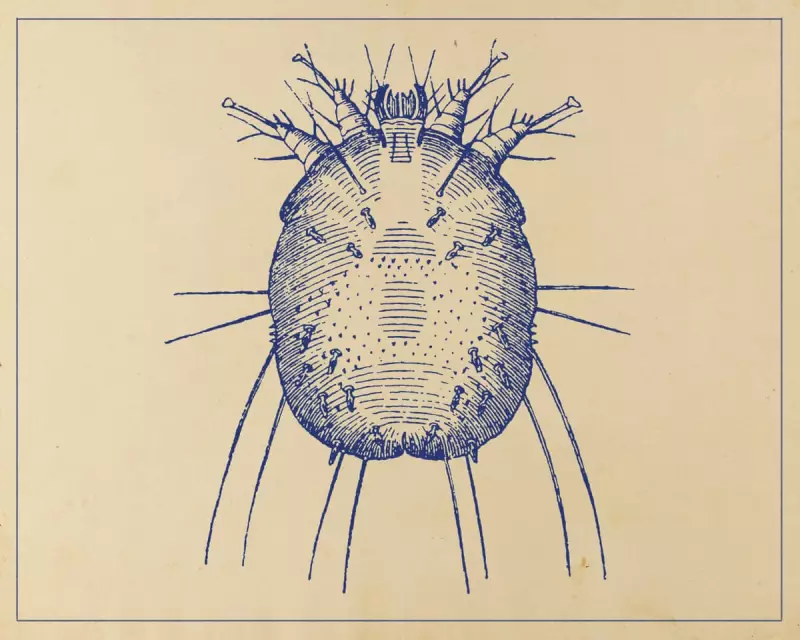

Scabies is caused by the human itch mite, Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, which burrows under the skin. The standard NHS treatment is permethrin cream, applied in two doses a week apart. However, correct application over the entire body for 12 hours is notoriously difficult, and treatment often fails if all close contacts are not treated simultaneously.

There has been discussion of possible mite resistance, but Professor Marks stresses that most "treatment failure is likely due to 'pseudo-resistance'" – incorrect application and untreated contacts. The situation was worsened two years ago by supply chain issues causing shortages of permethrin and another treatment, malathion.

A significant barrier to control is stigma. Dr Lea Solman, a consultant paediatric dermatologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital, identifies shame as a major obstacle. "It stops people seeking help quickly, and it stops them having the difficult conversations needed to ensure everyone gets treated at the same time," she explains.

This is keenly felt by young adults, who are disproportionately affected. The UKHSA report found 41% of 2024 diagnoses were in people aged 20 to 24. John, a 20-year-old in London, describes the mental toll: "My sleep has taken such a blow... this has taken a really big toll on my mental health and self-esteem." Professor Tess McPherson of the British Association of Dermatologists notes that university freshers' week has become a peak transmission time.

A System Under Strain and a Path Forward

The strain on the NHS is also a factor. Long GP waiting lists can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, with some sufferers reporting initial misdiagnoses of eczema or dermatitis. Dr Lewis Haddow, a consultant in sexual health in Kingston-upon-Thames, observes that scabies often falls between medical specialities. "Nobody really owns it," he suggests, which may hinder a coordinated public health response.

For now, those affected are often left to research and cope alone. The advice remains rigorous: treat all household and close contacts simultaneously, wash all bedding and clothing at 60C or higher, and quarantine non-washable items in sealed bags for at least three days. As cases continue to climb well above historical averages, the UK's battle against this ancient itch is very much a modern-day crisis.