Sue Noakes, a 64-year-old mother from West Sussex, experienced a profound sense of dread as she opened a letter confirming her worst fears: she had early-onset dementia. Despite long suspecting the terminal brain condition, seeing the diagnosis in writing was a devastating blow.

The Long Road to a Diagnosis

With a family history of the disease—having cared for her mother with Alzheimer's, her father with vascular dementia, and a brother with young-onset dementia—Sue was acutely aware of the warning signs. When her memory began to falter, she sought medical help and was referred to an NHS memory clinic.

Despite her clear symptoms, she claims the initial tests were deemed inconclusive and she was told it was 'too early' to diagnose her. Frustrated by the drawn-out process and desperate for answers to access medication sooner, Sue and a friend paid for a private brain scan in 2023, which provided the confirmation she both feared and needed.

'The quicker you can get on medication, the better it is,' Sue explained. 'It was such a long process... it's sad because we could pay for it, but there are many people who can't.'

Life After Diagnosis and a Devastating Loss

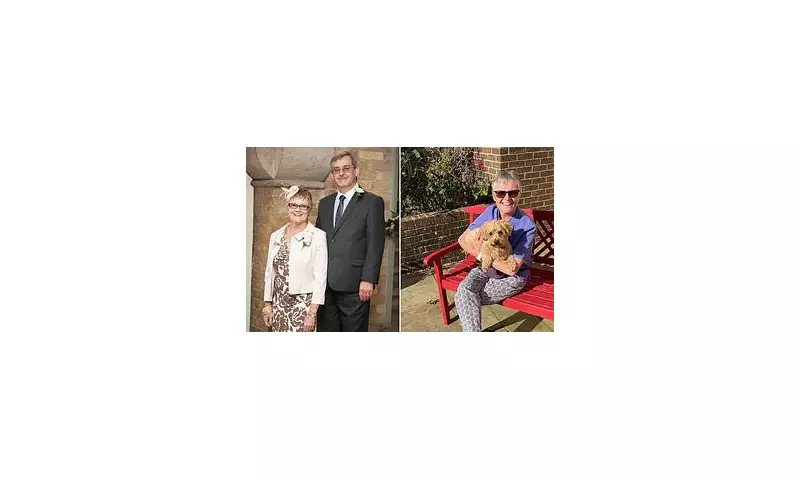

To cope with her diagnosis, Sue sought counselling and even trained to become a counsellor alongside her husband of 39 years, David. He became her rock, supporting her with daily tasks as her condition made completing chores and remembering names increasingly difficult.

Tragically, David died unexpectedly from a stroke in August, leaving Sue to navigate her dementia without her primary carer. 'I'd hoped I'd go first,' she said. 'He was amazing, loving, funny.' Now, her two adult sons batch-cook meals for her freezer, as she finds using a cooker or microwave challenging.

Sue describes her cognitive state as having a 'bird brain', flitting between tasks and easily distracted. She now uses speech-to-text technology on her phone to manage shopping lists, as her handwriting has become unreliable.

A Call for Change and Early Action

Sue's story emerges amid public concern over the NHS's capacity to handle the dementia crisis. Official estimates suggest there are 747,269 people with dementia in England, but only 496,715 have a formal diagnosis.

'It's the most infuriating disease,' Sue stated. 'If we don't do something about it and have a diagnosis earlier, then we are going to have a nation of people with Alzheimer's.' She stresses that dementia is not just an illness of old age, having met someone diagnosed at just 28.

She urges anyone with worries about their memory to seek checks, highlighting that symptoms could be due to other treatable issues like vitamin deficiencies. 'The sooner you address it, the quicker you can get medication, the quicker your family can help you, and therefore you'll be stronger, because you know what you're fighting.'

While advocating for more research and affordable medication, Sue tries to remain positive, walking her poodle and playing guitar. 'I still have a really good life,' she said. 'I would have rather had it with David, but it is what it is.'

A spokesperson for Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust said they recognise some people choose alternative options while waiting and that they actively signpost to support and offer therapies to help cope with a diagnosis.