A controversial US-funded hepatitis B vaccine study in Guinea-Bissau has been suspended, sparking a diplomatic and ethical dispute between African health authorities and American officials. The west African nation, one of the world's poorest, has halted the trial over concerns about scientific review and sovereignty, despite pushback from the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Sovereignty and Scientific Scrutiny at the Forefront

Quinhin Nantote, the recently appointed Minister of Health in Guinea-Bissau, confirmed to journalists that the trial has been "cancelled or suspended" due to inadequate scientific review. This decision follows a coup in November that led to leadership changes in the country. Nantote emphasised that the pause allows for a thorough evaluation of the study's ethics and methodology.

Jean Kaseya, Director-General of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, stated at a press meeting that a team of experts will travel to Guinea-Bissau to assist in reviewing the study. Officials from Denmark and the US have also been invited to participate. Kaseya highlighted that the halt is a matter of national sovereignty, asserting, "It's the sovereignty of the country. I don't know what will be this decision, but I will support the decision that the minister will make."

US Pushback and Credibility Challenges

In response, US health officials have contested the suspension. Andrew Nixon, an HHS spokesperson, insisted in a statement that "the trial will proceed as planned," accusing the Africa CDC of waging "a public-relations campaign aimed to shape public perception rather than engaging with the scientific facts." An HHS official further criticised the Africa CDC as "a powerless, fake organization attempting to manufacture credibility by repeating its claims publicly."

Kaseya countered these claims, noting he had spoken to senior HHS officials who were unaware of the statement, and pointed to the Africa CDC's pivotal role in managing global health outbreaks. The disagreement underscores tensions in international health research collaborations.

Ethical Concerns Over Study Design

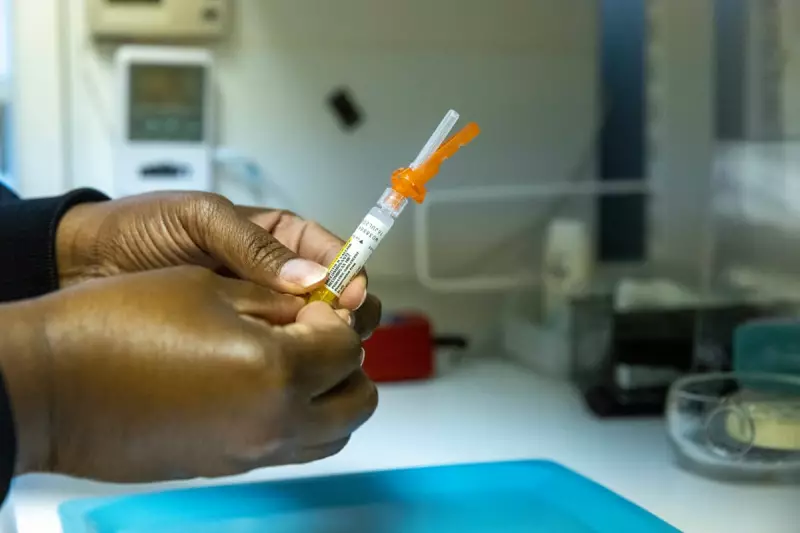

The study, led by Danish researchers, planned to administer hepatitis B vaccines to 7,000 infants at birth while withholding them from another 7,000 until six weeks of age to assess overall health effects. In Guinea-Bissau, nearly one in five adults and about 11% of young children have hepatitis B, increasing risks of severe illness and death.

Abdulhammad Babatunde, a medical doctor and global health researcher in Nigeria, criticised the design, stating, "This is not acceptable. To prevent things like the Tuskegee study and others, the control group has to get the standard of care, and the intervention group should get [potentially] better care." He emphasised the need for research that addresses African priorities, saying, "It's very important to fund research that Africans actually want. Africans want to solve Africa's problems, not satisfy the curiosity of the funders."

Approval and Oversight Issues

An early version of the study was approved by Guinea-Bissau's six-person ethics committee, Comité Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa em Saúde, on 5 November. However, subsequent updates were not reviewed, and the committee's interim director noted that the study did not disclose that some infants would go unvaccinated at birth, when the vaccine is most critical. Nantote expressed concerns that the ethics committee did not adequately address these issues.

The researchers did not appear to seek approval from ethics boards in Denmark or the US, despite the Helsinki declaration requiring oversight in both sponsoring and host countries. The HHS, researchers, and University of Southern Denmark did not respond to inquiries about ethical consultations.

Broader Health Challenges in Guinea-Bissau

Nantote and Kaseya both highlighted the severe health infrastructure gaps in Guinea-Bissau. Less than a quarter of the population has access to basic services like water and sanitation, with high rates of poverty, food insecurity, maternal mortality, and malaria. The World Health Organization recommends hepatitis B vaccination within 24 hours of birth, but infants in Guinea-Bissau currently receive it at six weeks, with plans to expand to all newborns by 2028.

Babatunde argued that funding should focus on improving vaccine coverage rather than experimental designs, stating, "The current reason why the vaccine is not achieving coverage in Guinea-Bissau is because there's no funding, and the funding should try to promote the vaccine, not use children as lab rats." He called for solidarity among African nations to support Guinea-Bissau's sovereignty and protect its children.

Gavin Yamey, a professor of global health at the Duke Global Health Institute, emphasised that "the most important voice" in any revised study should be Guinea-Bissau's ministry of health, responsible for safeguarding public health. As the review process unfolds, the suspension reflects ongoing debates over ethical standards, power dynamics, and autonomy in global health research.