Australia's foundational commitment to universal human rights is facing a profound test, both at home and abroad. Despite being a key architect of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the nation stands alone among liberal democracies for its failure to enact a domestic constitutional or statutory bill of rights.

A Global Assault and a Domestic Vacuum

The core principle that all people possess inalienable rights is under serious threat worldwide in 2025. Bombastic rhetoric from leaders and actions by militias are normalising the dangerous idea that certain groups are less than human, eroding decades of international order.

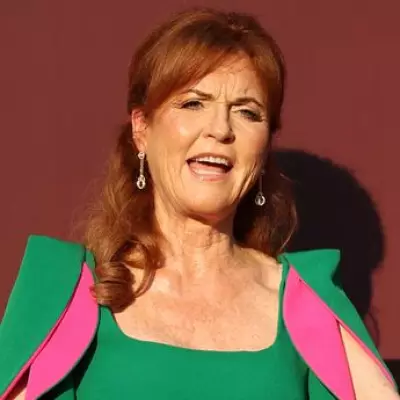

Yet, as Professor Julianne Schultz highlights, Australia's own position is contradictory and fragile. While Labor leader Doc Evatt helped midwife the UN declaration, Australia today relies on a patchwork of laws instead of a unified rights framework. This absence becomes starkly evident during national crises, such as the debates following the Bondi attack and the Adelaide Writers' Week controversy, where blame often overrides principle.

Rights Subject to Political Whim

The Australian approach to human rights protection has repeatedly proven vulnerable to political expediency. Legislation has been voided to allow racially charged laws, like the Northern Territory intervention, to pass. Even states that have enacted rights charters have readily suspended them for specific groups, frequently First Nations peoples.

A recent example underscores this fragility. In South Australia, a bill affirming the right to artistic freedom, promised during an election campaign, was introduced in 2025. Parliament, however, ran out of time to pass it. This legislative failure raises questions about whether such protections could have altered the contentious public debates around creative expression.

In response to growing international instability, the government appointed former attorney general and sitting MP Mark Dreyfus as an International Human Rights Envoy last year. Critics argue his advocacy should begin at home, championing a statutory bill of rights to strengthen both domestic protections and Australia's global standing.

The Erosion of Empathy in a Data-Driven World

The debate extends beyond legal texts into the fabric of daily life, where technology and bureaucracy are eroding human empathy. In an AI-mediated, tick-box world, the biases of systems increasingly exclude people, imposing a technocrat's view of order where shades of grey vanish.

Schultz recounts two personal experiences that reveal this 'banal cruelty'. When contacting Centrelink about a deceased person, the operator, bound by a script, had no protocol to offer condolences—only to continue demanding data. Separately, a highly educated colleague expressed a preference to avoid 'human intervention' when contesting a fine, a sentiment that alarms the author.

"If we give up on human intervention, the technocrats have won," Schultz warns. The fight for human rights is also a fight to preserve empathy and nuance against systems designed solely for efficiency and profit. In a world with unprecedented capacity for self-destruction, it is a fight Australia, and the world, cannot afford to lose.