The Historic Power Shift: From Veto to Delay

For centuries, the House of Lords held an absolute veto over legislation passed by the House of Commons. This formidable power was dramatically curtailed following a major constitutional crisis in 1909, when the Lords blocked Chancellor David Lloyd George's radical budget. The ensuing political storm led to a general election fought on the issue of Lords reform, resulting in the Liberal government's landmark Parliament Act of 1911.

This legislation fundamentally altered the balance of power between the two chambers, stripping the Lords of their veto in nearly all circumstances and replacing it with a delaying power. The 1911 Act was further amended in 1949, reducing the Lords' ability to delay legislation to just one year. Under these rules, if the Commons passes a bill that the Lords then delays for more than a year, the legislation can be reintroduced in the following parliamentary session and enacted without the Lords' consent.

A Rarely Used Constitutional Mechanism

The Parliament Act procedure has been invoked on only seven occasions throughout its century-long existence, typically for deeply contentious social issues of their time. The most recent applications were in 2000 to equalise the age of consent for homosexual acts to 16, and in 2004 to pass the Hunting Act that banned foxhunting with dogs.

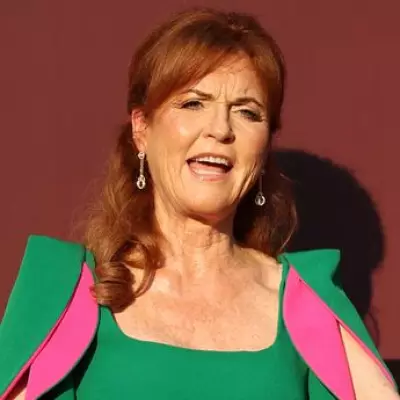

Now, supporters of Kim Leadbeater's private member's bill to legalise assisted dying in England and Wales are exploring whether this rarely used constitutional mechanism could help them overcome anticipated opposition in the House of Lords. With the current parliamentary session expected to conclude in May, and the bill facing over 1,000 amendments alongside slow progress, proponents are preparing contingency plans.

Uncharted Territory for Private Member's Bills

Applying the Parliament Act to a private member's bill would be unprecedented and presents significant procedural complexities. Unlike government legislation, private member's bills lack automatic parliamentary time allocation and depend on either ballot success or government cooperation.

For the Parliament Act to potentially apply, the assisted dying bill would need to pass the Commons but fail in the Lords by the session's end. Supporters then face two possible routes to revive it:

- Ballot Success: A supporter could reintroduce the bill in the next private member's bill ballot. However, this depends entirely on chance, with hundreds of MPs entering and only the top five slots offering realistic prospects of parliamentary time.

- Government Intervention: The government could allocate time for the bill in the next session while maintaining its official neutrality. This would likely provoke significant controversy, including opposition from Labour backbenchers who disagree with assisted dying legislation.

Strict Conditions and Potential Complications

Should either pathway succeed, the Parliament Act imposes strict conditions. The revived bill must be identical to the version originally passed by the Commons, with no amendments permitted during its second passage through the lower house. While some constitutional experts suggest limited circumstances might allow minor amendments, this remains legally uncertain.

The process would require the bill to pass second and third readings in the Commons again, after which peers could still attempt to block it. At that point, the Parliament Act could be invoked to bypass the Lords entirely and send the legislation for royal assent.

Political Calculations and Constitutional Precedent

The government's position adds further complexity. While maintaining strict neutrality on the assisted dying bill itself, Labour leader Keir Starmer personally supports legalisation. This creates potential for political pressure to secure government time for the legislation, particularly if framed as a democratic necessity following Lords obstruction.

However, such intervention would likely spark significant controversy, potentially turning some supporters into opponents and creating divisions within parliamentary parties. If neither ballot success nor government cooperation materialises, supporters acknowledge they would have exhausted all constitutional avenues for advancing the legislation in the current parliament.

The assisted dying debate thus presents not only profound ethical questions but also a potential test case for how Britain's constitutional arrangements handle deeply divisive social legislation when the elected Commons and appointed Lords reach fundamental disagreement.