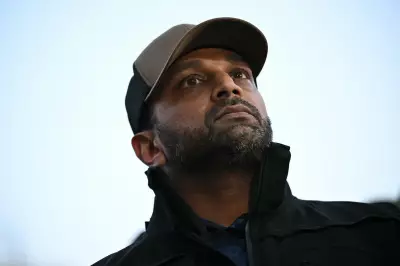

In a quiet military cemetery in northern Taiwan, a man performs a solemn duty that bridges decades of separation and a deep political divide. Liu De-wen, 58, carefully retrieves a jade green urn from a shelf, cradling it gently. "Grandpa Lin, follow me closely," he whispers. "I am bringing you back home to Fujian as you wished. Stay close."

A Lifelong Mission Born from Compassion

For the past 23 years, Liu has dedicated himself to a poignant task: helping the remains of hundreds of people, primarily former soldiers, make their final journey from Taiwan back to their ancestral homes in mainland China. The ashes belong to individuals like Lin Ru Min, a fisherman who was 103 when he died in Taiwan, far from his village in China's Fujian province.

Lin's story is a painful echo of a turbulent history. At the end of the Chinese civil war in the late 1940s, he was a young fisher with a family when he was forcibly taken by retreating nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) troops. He was conscripted and brought to Taiwan, unable to return home for almost half a century. Historian Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang notes that tens of thousands were "literally kidnapped to Taiwan this way" from coastal communities.

Liu's work began in his thirties after he moved into a community built for KMT soldiers and later became its borough chief. "There were over 2,000 single veterans just in my community who had no wives or families here in Taiwan," Liu recalls. He was deeply moved by their longing, witnessing them sit for hours during Chinese New Year, facing the direction of their hometowns. Their plea was simple: "Borough chief, could you please take me home?"

Navigating History and Political Sensitivities

Liu's mission operates at the complex intersection of personal grief, family separation, and the fraught political relationship between Taiwan and China. When travel bans were lifted in the late 1980s, it was too late for most of the hundreds of thousands of remaining veterans to return permanently. Only about 2% ever made it back. As Professor James Lin of the University of Washington explains, their original homes had changed dramatically, and many had built new lives in Taiwan.

Yet, the wish to be buried in ancestral soil remained strong. Before he died, Lin Ru Min expressed his final wish to his niece's daughter, Chen Rong, leading her to seek Liu's help. Liu's process is meticulous and respectful. He locates graves—sometimes in overgrown mountain areas—handles the complex paperwork, and personally escorts the urns to China.

He carries the urn in a backpack worn on his front, a sign of deep respect. "It's not a commodity, it represents an elder with a soul and a life," he says. His social media documents the journeys, showing the urn accorded its own seat on transport and its own hotel bed.

A Bridge Between Two Shores

Liu does not charge for his services and states he receives no financial aid from either the Taiwanese or Chinese governments, though he is vague about funding. His work has earned him the nickname "ferryman of the souls" in Chinese state media, which extensively covers his missions. This coverage serves a dual purpose: while highlighting genuine human stories, it also aligns with Beijing's narrative emphasising familial ties across the strait to promote its goal of unification.

Professor Lin notes that while many in mainland China sympathise with the old soldiers' plight, the narrative is useful propaganda for Beijing. This exists in a context where over 60% of people in Taiwan identify solely as Taiwanese, and a large majority oppose unification.

For Liu, the politics seem secondary to the human connection. He describes people on both sides as kin who "share the same origins and the same heritage." His primary concern is peace and building a bridge. "What I care deeply about is building this kind of bridge for veterans to go home," he states.

After collecting Lin's urn, Liu wraps it in red and gold cloth, preparing it for the journey. Chen Rong weeps, saying, "We are going home... Please bless us with health and safety." In this simple, profound act, Liu De-wen navigates the weight of history, offering a final homecoming to those caught in the tides of a conflict that shaped their lives.