The fundamental question of what it means to be British has been thrust to the forefront of political discourse, ignited by a fierce row over the citizenship of British-Egyptian activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah. The debate, exposing a widening fault line in perceptions of national identity, follows calls from the Conservatives and Reform UK to strip Abd el-Fattah of his UK passport over offensive social media posts made over a decade ago.

A Controversial Arrival Sparks Political Firestorm

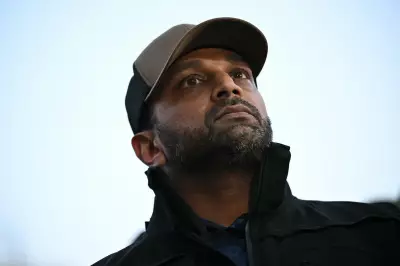

Alaa Abd el-Fattah's arrival in the UK last week, after a decade imprisoned in Egypt, was swiftly overshadowed by the resurfacing of racist and inflammatory tweets he posted between ten and fifteen years ago. The posts included calls to "kill all Zionists" and to burn Downing Street during the 2011 riots. Abd el-Fattah has since apologised for these remarks.

However, the subsequent demand for the revocation of his citizenship has created acute political discomfort. Both Labour and the Conservative parties have, through successive governments, campaigned for his release—a consular priority since he was granted UK citizenship in 2021. Critics argue the intensity of the calls from figures like Nigel Farage and Shadow Home Secretary Chris Philp is amplified by Abd el-Fattah's status as a dual national from a minority ethnic background.

Downing Street has maintained its position, asserting on Monday that Abd el-Fattah has a right to consular support like any other British citizen. This stance underscores a recurring reality: many Britons facing detention abroad, like Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Hong Kong media tycoon Jimmy Lai, hold dual nationality or foreign heritage.

The Many Pathways to a British Passport

The case highlights the diverse legal routes to British citizenship. Abd el-Fattah was entitled to his passport under the British Nationality Act 1981 because his mother is a British national. Similarly, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was naturalised after living in the UK and marrying a British man, while Jimmy Lai gained citizenship in 1996 before the Hong Kong handover.

For most, these routes are unremarkable, with Britishness rooted in shared values like obeying the law and contributing to society. Yet, a new report by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) signals a profound shift in public attitude. It found that 36% of people now believe you must be born in the UK to be truly British, a near doubling from just 19% in 2023.

Mainstream Politics and a Shifting Overton Window

The approaches of Reform UK and the Conservatives to this case demonstrate how the boundaries of acceptable political debate on national identity have moved. Both parties have recently faced criticism for endorsing policies that could lead to the mass deportation of people living legally in the UK.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has sought to position this debate at the core of his government, framing the next election as a battle between his "progressive patriotism" and Nigel Farage's "incendiary nationalist politics." However, some within his own party privately contend he has been too hesitant to articulate this vision during moments of crisis, such as recent far-right marches in Westminster.

As the IPPR concludes, defining a cohesive national identity "cannot be outsourced to a few speeches or policies." It requires the Prime Minister to consistently articulate a compelling story of what Britain is and what it aspires to be—a task made ever more urgent by the deepening divisions this case has revealed.