World Cup Preparations Displace Mexico City's Poor, Slashing Livelihoods

Preparations for the 2026 FIFA World Cup in Mexico City are cutting deeply into the livelihoods of sex workers and street vendors operating near the iconic Azteca Stadium. As the Mexican capital undergoes rapid renovations to welcome global sports fans, many of the city's most vulnerable residents face slashed wages and forced displacement, highlighting the social costs of mega-events.

Sex Workers See Earnings Halved Amid Construction

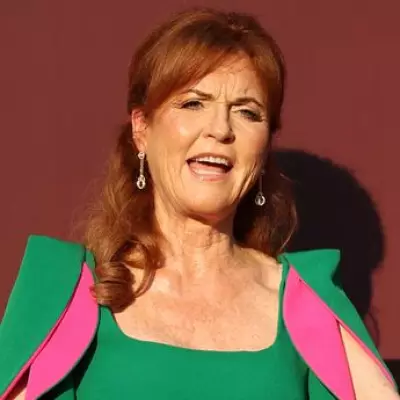

Montserrat Fuentes, a 42-year-old sex worker, has stood on the same street corner for two decades, but her usual Friday night rush of clients has vanished. The busy Calzada de Tlalpan avenue, home to around 2,500 sex workers, is now lined with construction as part of World Cup preparations. Fuentes reports that her earnings have been cut by more than half due to projects like a new bike lane, with large dividers blocking cars from pulling over to negotiate services.

Elvira Madrid Romero, president of the sex worker advocacy group Street Brigade, criticizes the government's focus on profit over people. "Tourists are coming to celebrate at the expense of the poor," she said. Sex work, not criminalized in Mexico, provides an economic lifeline for approximately 15,000 people in the capital, including transgender women who face discrimination in other sectors. Many single mothers in Madrid's coalition struggle to afford food and rent, with government aid offers falling short of their needs.

Street Vendors Face Impending Displacement

For street vendors like Esperanza Toribio Rojas, a 68-year-old smoothie seller, displacement is no longer a hypothetical threat but an impending reality. Hundreds of vendors operate in tunnels beneath the avenue, accessing metro stations that serve the World Cup stadium. These merchants revitalized once crime-ridden passages, but now face removal under the city's "Steps to Utopia" initiative, aimed at creating safe spaces with cultural activities for the competition.

Jaír Torruco, a local merchants' leader, estimates that 100 to 200 vendors have already been pushed out, while around 250 others resist government offers they deem insufficient. Toribio expressed frustration, stating, "Today the government sees this place, they see that there is life, and they want to take it for themselves. This is our heritage." Vendors offered temporary spaces report struggling to make ends meet, with many doubting promises of a return post-World Cup.

Global Pattern of Social Cleansing in Mega-Events

The situation in Mexico City mirrors a global pattern where major sporting events often lead to social cleansing, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. During the 2024 Paris Olympics, African migrants and homeless people were bused out of the city, while the 2014 World Cup in Brazil saw tens of thousands evicted from their homes. In Mexico, tensions are already simmering due to an influx of foreigners pricing locals out of neighborhoods, exacerbated by limited government action on housing shortages.

Fuentes, who took a second job selling food to pay rent, fears repeat displacement after being pushed out of downtown food sales two decades ago. "Even if we raise our voices, we can’t really do anything," she lamented. Despite negotiations and promises from Mexico City Mayor Clara Brugada for designated meeting points and aid, many workers report seeing no tangible support, refusing to leave their workplaces.

The 2026 World Cup, co-hosted by Mexico, the United States, and Canada, is projected to generate $3 billion in economic activity in Mexico. However, with over half the workforce in informal employment, concerns mount that precarious workers will be left behind. As construction continues, the hope among displaced communities is for a return to normalcy after the event, but uncertainty looms over their futures.