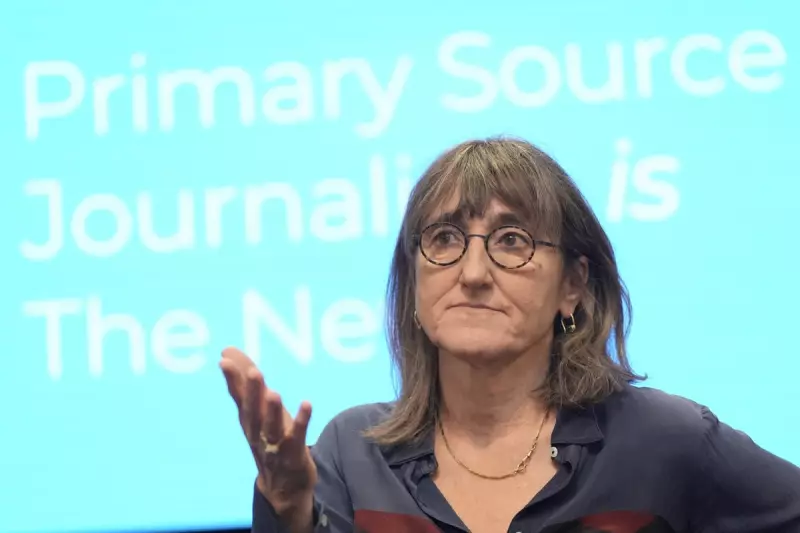

Outrage rather than reasoned argument is driving rapid changes to social media legislation, according to a leading children's rights campaigner and filmmaker. Baroness Kidron, founder of the digital safety organisation 5Rights, has told the Press Association that recently enacted laws have consistently failed to meet the expectations of campaigners working to protect young people online.

The Crisis of Online Safety

Baroness Kidron, whose film credits include Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason, delivered a stark assessment of the current landscape. "We're winning the crisis – it's a crisis," she stated. "I don't think we're winning the argument, really. What we're doing is we're winning the outrage. And the Government will probably out of political expediency do the wrong thing which is, just bring in a ban without thinking about the political context or the regulatory context."

Legislative Action and Amendments

The crossbench peer has tabled a suite of amendments to the Crime and Policing Bill, which is scheduled for debate in the House of Lords on Tuesday. These amendments aim to better preserve social media data that could prove crucial to authorities investigating child deaths. This legislative push comes alongside her recent vote for an under-16s social media ban as part of the Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill last Wednesday, though she has simultaneously called in the Lords for "a better answer than a ban" that tackles "root harms" while still permitting children internet access.

The Government is currently consulting on measures designed to bolster children's wellbeing online. These potential measures could include establishing a minimum age for social media access and removing features considered addictive. Baroness Kidron explained her support for the ban vote by noting that lawmakers "have to have something" in place to protect children's wellbeing, drawing a powerful analogy: if some digital platforms were "a toy or a fridge or an airbag, they would be recalled by now." She warned that technology firms have "created a state of exceptionality which actually translates into a state of lack of liability."

The Data Preservation Challenge

While Ofcom already possesses the authority to instruct social media companies to preserve data concerning a deceased child when requested by a coroner, Baroness Kidron asserts this mechanism "isn't working" effectively. She points to coroners and investigators being unaware of their powers under the Online Safety Act and has called for these data preservation notices to become automatic.

"Whatever the circumstances are of a child's death, the coroner, the police and parents need to know what's been going on," she emphasised. "This is not about apportioning blame to another user, to the site, to the child. It's about having the information so that one can come to a conclusion about what the contributing factors are. And I think there's a fundamental problem here which is, the virtual world, I think we used to conceive it as 'other' and 'different', but the virtual world is increasingly entangled with the real world and certainly for young people. And the same rules apply – if someone died, you'd look around the room, you'd look at what they were doing for the last few days, etcetera. And the same rules must apply online. So, I think people get confused because of the word 'data', but data isn't 'data', data's 'information'. It's the circumstances."

Families Fighting for Answers

Ellen Roome, who believes her 14-year-old son Jools Sweeney died while attempting an online challenge, has echoed these concerns about systemic failures. She told PA that families are spending "years fighting for answers that should never have been denied." Ms Roome observed: "Things are moving more quickly now because the scale of harm has become impossible to ignore. Too many children have been hurt or lost, and too many families, including mine after Jools died, have spent years fighting for answers that should never have been denied. Progress is welcome but it is still not fast enough."

She highlighted a critical flaw in the current system: "Laws only protect children if they are actually used and right now, vital digital evidence is still being lost in the early hours after a child's death. Until data is preserved automatically and investigations are digitally competent from the outset, we will continue to react to tragedy rather than prevent it, and social media companies will remain beyond accountability because the evidence of what children were shown no longer exists."

Government Response

A Government spokesperson responded to these concerns, stating: "We've been clear – we will take action to make sure children have a healthy relationship with mobile phones and social media. This is a complex issue with no common consensus and it's important we get this right. That's why we are launching a consultation to seek views from experts, parents and young people to ensure we take the best approach, based on the latest evidence."

The spokesperson addressed the specific issue of data preservation: "Families who have suffered the devastating loss of a child must never feel that the system is working against them. That is why the Online Safety Act compels companies to share data and cooperate fully with coroners' inquiries where there is evidence of a link between a child's death and their social media use. We have strengthened this further by giving coroners the power to require platforms to preserve data immediately, so vital evidence cannot be deleted. We will continue to monitor these powers and will not hesitate to act where evidence shows we need to go further."