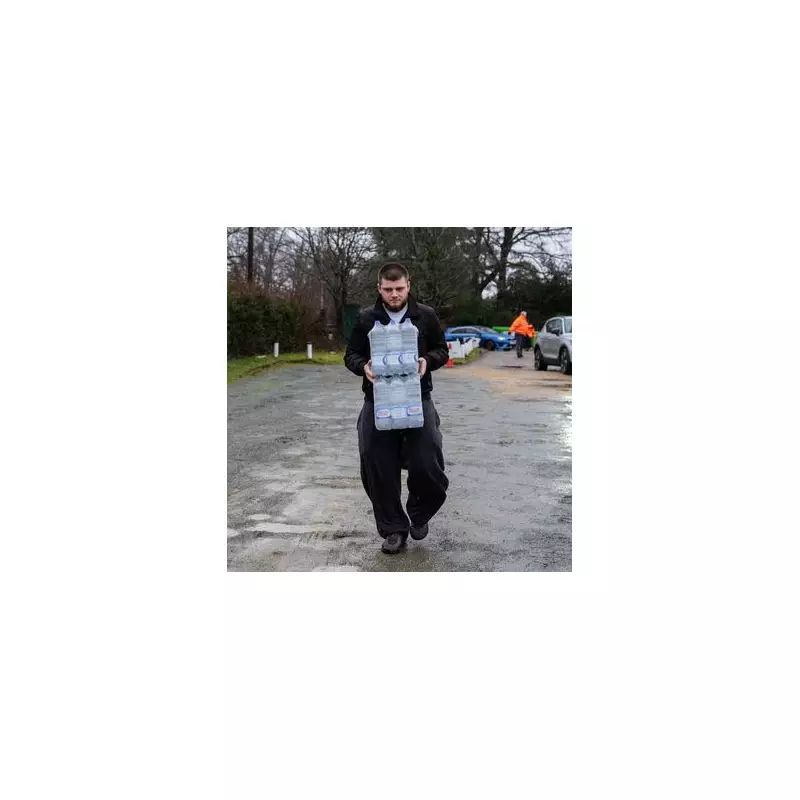

The recent water supply crisis in Kent, which left around 30,000 properties scrambling for emergency supplies, is symptomatic of a far deeper malaise within England's privatised water industry, according to a damning critique. The sector stands accused of prioritising shareholder dividends over public and environmental health, extracting an estimated £85 billion while failing to prevent the degradation of the nation's waterways.

A System Rigged for Profit, Not People

While companies frequently cite external factors like weather for operational failures, the fundamental issue lies in the structure created by privatisation in the late 1980s. Although the sell-off under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher initially spurred investment, it ultimately created what critics call a "licence to print money." New owners loaded the utilities with enormous debts to finance their purchases, securing guaranteed returns from a captive customer base.

Today, the industry is largely owned by distant, mega-rich investors and pension funds from Australia, Hong Kong, Canada, and beyond. Customers, unable to switch providers as they can with energy or supermarkets, are effectively prisoners. For years, the economic regulator, Ofwat, was criticised for having "as much bark as a chihuahua," failing to robustly defend consumer interests until recently.

Sewage, Salaries, and a Looming Bailout

The consequences are starkly visible. Rivers and seas face repeated discharges of raw sewage, turning them into what campaigners label "cesspits." Meanwhile, executive pay remains controversially high. David Hinton, the boss of South East Water, received a £400,000 salary plus a £50,000 overtime payment for preparing a price hike that raised customer bills by 20%.

The financial model is now under severe strain. Thames Water, burdened by colossal debts, is described as a "debt-laden-dead-man-walking," with the implicit understanding that the taxpayer would ultimately be forced to rescue it due to water's essential nature. This prospect has intensified calls for systemic change.

The Growing Call for Public Ownership

The proposed solution from many critics is clear: renationalise. They argue that if Labour's effective renationalisation of railways can serve as a blueprint, then water—a natural monopoly—should follow. They point out that nine out of ten countries globally manage water in public ownership.

The current Labour government has begun tackling these long-standing issues. True success, however, will be measured by tangible outcomes: rivers safe for swimming, anglers free from the risk of toxic catches, and households receiving reliable, affordable water without the dread of an outrageous bill. Until then, the debate over who truly benefits from England's water will rage as fiercely as the sewage spills polluting its coasts.