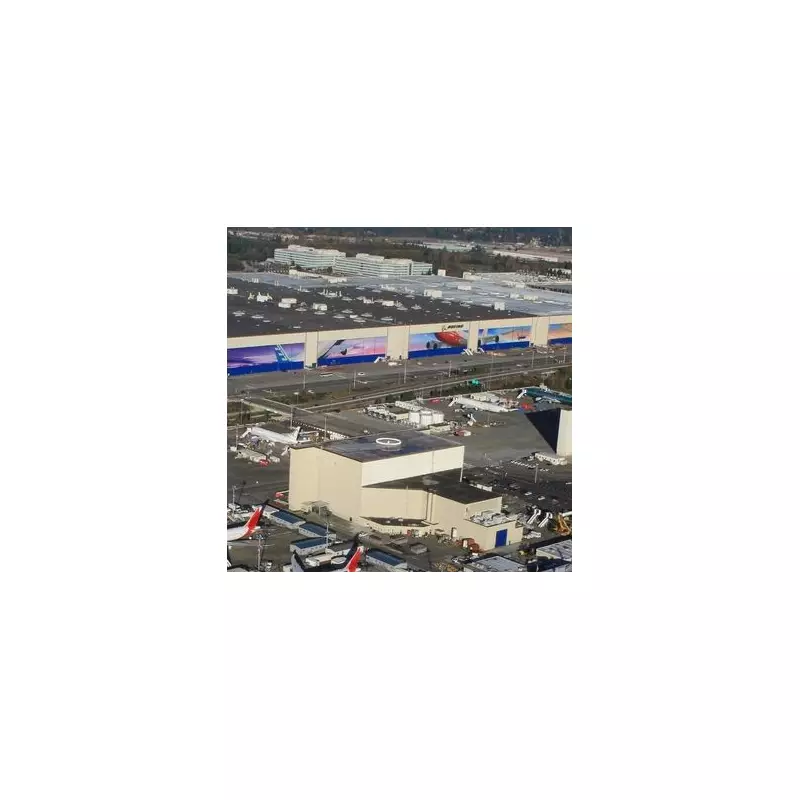

In the world of manufacturing, one facility stands alone in sheer, staggering scale. The Boeing Factory in Everett, Washington, holds the undisputed title of the world's largest building by volume, a colossal structure so vast that it once generated its own indoor weather systems and is spacious enough to swallow the entire original Disneyland resort.

A Monumental Vision for the Jumbo Jet

The origin story of this industrial leviathan is inextricably linked to the birth of an aviation icon: the Boeing 747. In the 1960s, Boeing's then-President William M. Allen recognised that producing the groundbreaking "jumbo jet"—a plane two-and-a-half times larger than its contemporaries—would require a revolutionary new manufacturing space. After evaluating several sites, the company settled on a disused military airfield in Everett, just 22 miles from its Seattle headquarters, a location championed by 747 chief engineer Joe Sutter.

Construction was a feat of breakneck speed and immense effort. The building was completed in just over 12 months, at a cost exceeding $1 billion—a sum that, according to Airways magazine, surpassed Boeing's entire net worth at the time. Workers moved 4 million cubic yards of earth, a task so large it required a dedicated railway line to haul the material away. The result was a 98-acre, 472 million cubic foot facility that immediately dwarfed all other buildings on the planet.

Life Inside the Behemoth

The scale of the Everett factory is almost incomprehensible. To put it in perspective, the original 85-acre Disneyland in Anaheim would fit comfortably within its walls. Its immensity was such that in the early days, moisture would accumulate under its 90-foot-high roof, forming clouds—a microclimate phenomenon only later solved by modern air conditioning.

Today, the factory is a buzzing city within a city. Approximately 36,000 employees work across three shifts daily. Not all are building aircraft; the site employs its own fire brigade, runs banking and medical facilities, childcare centres, and a water treatment plant. To navigate the vast floor without disrupting production, staff use an intricate two-mile network of underground tunnels, travelling by a fleet of over a thousand bicycles and several vans.

On the production floor, 26 overhead cranes glide along 31 miles of rail, moving aircraft down the assembly line at a pace of about an inch and a half per minute. The final painting stage alone can take up to a week, consuming around 454 litres of paint for a 747.

Expansion, Tours, and Legacy

The factory has grown significantly since 1967, with major expansions in 1978 for the 767 and 1992 for the 777. Recent additions support robotic assembly for the 777 fuselage and composite wing production for the new 400-seat 777X, with the first delivery predicted for 2027. To date, the plant has produced over 5,000 wide-bodied aircraft.

Its allure isn't limited to workers and engineers. Public tours have become a major attraction, with 239,579 visitors paying $20 each for the experience in 2024 alone. Tourists like David and Georgiana King from Sussex have returned to witness the evolution, noting the introduction of the 787 Dreamliner since their first visit a decade ago.

Bonnie Hilory, executive director of the Future of Flight Foundation, perhaps best encapsulates the site's essence, calling it Boeing's "best product" and summarising it in one word: "scale." It is a testament to human ambition—a building so enormous it defies belief, where the weather indoors was once part of the daily forecast and the dreams of flight are built on a truly gargantuan scale.