A stark new survey has laid bare the devastating impact of the housing crisis on children's education, revealing that more than half of teachers in England have worked in a school with homeless pupils in the past year.

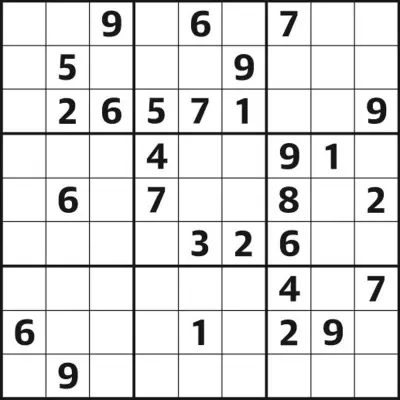

Survey Reveals Scale of Classroom Crisis

The major study, organised by the homelessness charity Shelter, involved 7,127 state school teachers. It found that 52% had experience of a school with children who were homeless. Nearly a third (31%) said a child they personally taught was homeless, with a further 20% aware of homeless children in their school they did not directly teach.

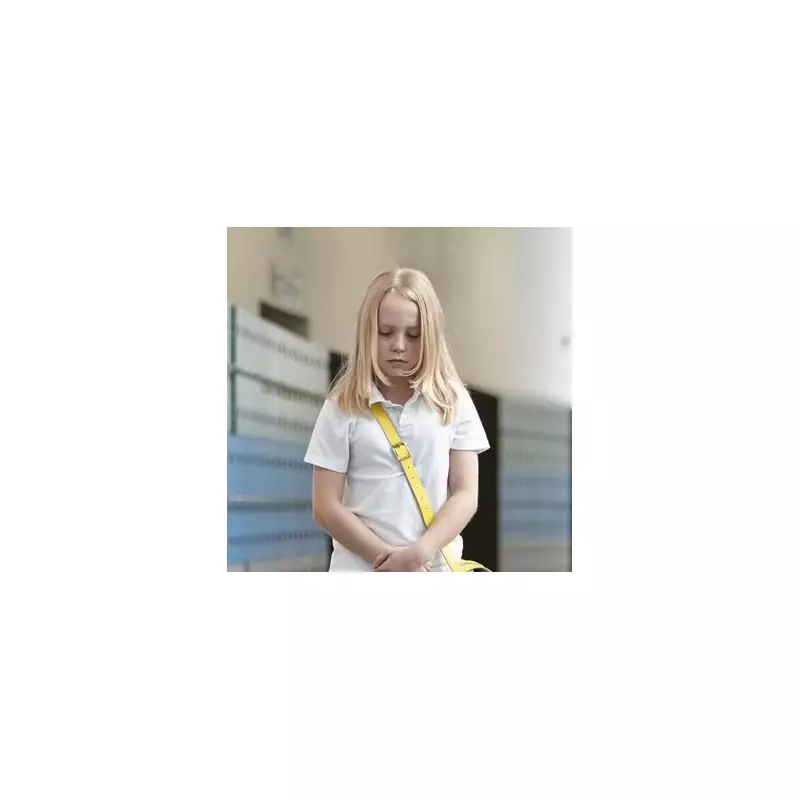

Children without a safe, secure home are suffering from exhaustion, missing school days, and experiencing poor mental health, the data shows. The disruption of being moved between temporary housing at short notice is a key factor identified by the charity.

Exhaustion, Absence, and Failing Grades

The consequences for a child's education and wellbeing are severe and widespread. An overwhelming 92% of teachers reported that homelessness leads to pupils arriving at school tired. Furthermore, 83% said it had caused children to miss school entirely.

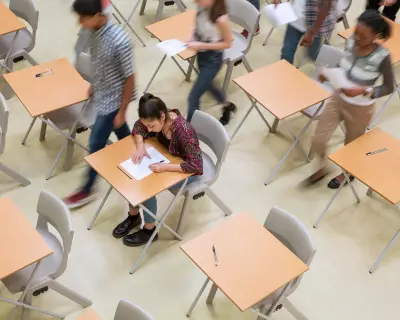

Perhaps most damning for future life chances, three quarters (75%) of teachers stated that being homeless had directly resulted in children performing poorly in assessments or exams. The same proportion said homelessness had a significant impact on the mental health of the children they teach.

More than 175,000 children are currently living in temporary accommodation across England, according to Shelter. Families are regularly shuttled between B&Bs, hostels, and other unsuitable housing, often miles from a child's school.

Calls for Action and Government Response

Sarah Elliott, chief executive of Shelter, said: “The housing emergency is infiltrating our classrooms and robbing children of their most basic need of a safe and secure home. Children shouldn’t have to try and balance their studies with the horrific experience of homelessness.” She called for the government to set a national target to build 90,000 social rent homes a year for ten years.

Teaching unions echoed the urgent need for intervention. Matt Wrack, General Secretary of the NASUWT, warned that a child's future life chances are being put at risk, while Paul Whiteman of the NAHT said the figures showed the scale of the challenge despite some welcome measures in the government's new child poverty strategy.

Last week, the Labour party unveiled a new National Plan to End Homelessness, pledging to halve street homelessness and end the use of B&Bs for families. The government's own strategy includes an £8 million emergency fund to stop the unlawful placement of families in B&Bs beyond six weeks.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) stated: “No child should be trying to learn without the security of a settled home.” They pointed to changes allowing schools to support homeless pupils earlier and a comprehensive homelessness strategy backed by record funding.

The human cost is illustrated by the experience of Ayeasha Pemberton, 47, from London, who was homeless with her son for 12 years. They were moved between five temporary properties, one of which had a collapsing ceiling due to flooding. At one point, they were placed so far from her son's school he could not live with her during the week. She described the experience as “really depressing and stressful,” and said the years of instability have made it hard for her son to focus on his upcoming GCSEs.