The cinematic landscape is currently dominated by a poignant and powerful theme: profound, elemental grief. At the heart of this trend lies a critical debate: when does a film's exploration of loss become profound art, and when does it tip into emotionally manipulative 'grief-porn'? This question is particularly pertinent for two recent, high-profile adaptations: Chloé Zhao's 'Hamnet' and the film version of Helen Macdonald's 'H Is for Hawk'.

The Unbearable Weight of Feeling

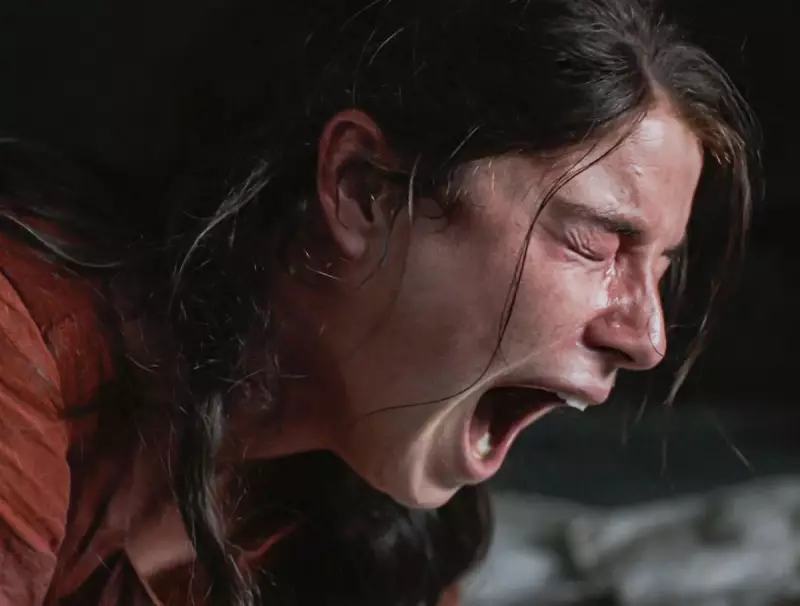

The core of the debate rests on a circular logic. A film about grief is often judged by the perceived depth of its characters' emotion. The audience, in turn, validates its artistic merit by the intensity of their own mirrored response. If you are left profoundly moved, it is art. If you find the emotional display domineering and leave dry-eyed, the work can be dismissed as manipulative. This framework offers little room for middle ground.

This is the central challenge facing Hamnet, the Maggie O'Farrell adaptation starring Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal. On a technical level, it demands to be seen as art. The leads deliver performances of magnetic believability, the cinematography is sumptuous, and the dialogue is spare and intelligent. The story, which cannot be a spoiler given its historical basis, follows Agnes (Buckley) and William Shakespeare as they grapple with the death of their 11-year-old son, Hamnet, from the plague.

The film establishes several principles of screen grief. It posits that women feel more deeply, particularly the parental bond, and possess a stronger connection to the natural world and unspoken magic. Buckley's Agnes curls in tree roots, breathless with maternal anxiety spliced with witchy premonition. Similarly, in H Is for Hawk, Claire Foy's Helen retreats into an isolated communion with a goshawk after her father's (Brendan Gleeson) sudden death. Her obsessive training of the bird, Mabel, becomes a stalwart refusal to let her father be gone.

Birds as Harbingers: From Freedom to Death

A fascinating through-line in these narratives is the use of avian symbolism. However, the meaning has starkly shifted. Where birds once signified liberation, in these modern grief narratives they are unequivocal symbols of death. Agnes has a hawk; Shakespeare's first overture is to craft her a glove from his family's trade. (Bird enthusiasts have noted the film uses a Harris's hawk, an anachronism for 1580s England).

This ornithological motif extends to other recent films. Tuesday features Julia Louis-Dreyfus grappling with her daughter's impending death, accompanied by a size-altering macaw. The Thing with Feathers adapts Max Porter's novella, with a crow embodying grief for a bereaved father played by Benedict Cumberbatch. The camera lingers on the birds' eerie watchfulness and sudden movements, evoking discomfort rather than awe. The imagery becomes prescriptive: to appreciate these films is to find majesty in the creature's 'deathiness' and autonomy.

Tuesday stands apart by allowing humour into the void. Louis-Dreyfus's portrayal of avoidance—selling taxidermy rats, needing a wee—as her daughter tries to secure her attention to die, is genuinely funny. This touches on a broader truth of grief: the absurdity and brutal normality that intrude upon agony. Yet, most grief films brook no sustained comedy; laughter is as unwelcome in this genre as it is in traditional porn, perhaps serving as the ultimate litmus test between art and exploitation.

Gendered Grief and the 'Feminine Consciousness'

The discourse reveals a stark gendered divide in how screen grief is framed. The inarticulate silence of a grieving woman is feminine mystique and depth. For a man, as seen in The Thing with Feathers, similar inarticulacy can be read as masculine shortcoming. Director Chloé Zhao stated that making Hamnet revealed how 'feminine leadership' draws strength from intuition and community. This creates another circular argument: Agnes's grief cycle largely displays isolation and raw pain, yet those feminine qualities must be present because a woman is feeling them.

Ultimately, whether these films are classified as grief-porn or grief-art may be less important than the conversation they spark. They hold a mirror to our expectations of emotional authenticity, the symbols we use for mortality, and the different narratives we allow for men and women in pain. The debate itself proves that cinema's power to make us feel—or question why we don't—remains undiminished.