A major initiative designed to force climbers to remove rubbish from the slopes of Mount Everest has been abandoned after authorities discovered widespread cheating, leaving the world's highest peak buried in persistent waste.

The Failed $4,000 Deposit Scheme

Introduced in 2014, the programme required every mountaineer scaling beyond Everest's Base Camp to pay a $4,000 (£2,964) refundable deposit. They would only get their money back if they returned to base with at least 8kg (18lbs) of waste, aiming to tackle decades of accumulated debris like oxygen cylinders, abandoned tents, and human excrement.

However, after 11 years, the scheme has been scrapped. Tshering Sherpa, CEO of the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), told the BBC the rubbish problem has 'not gone away'. Climbers found a simple loophole: instead of collecting the most problematic waste from the treacherous higher camps, they gathered easier-to-access trash from lower down the mountain.

The Shocking Scale of Everest's Waste Crisis

The failure of the deposit system is a significant blow to efforts against an environmental crisis. Tourists and climbers in the Sagarmatha National Park bring an estimated 1,000 tonnes of waste into the region annually, much of which never leaves.

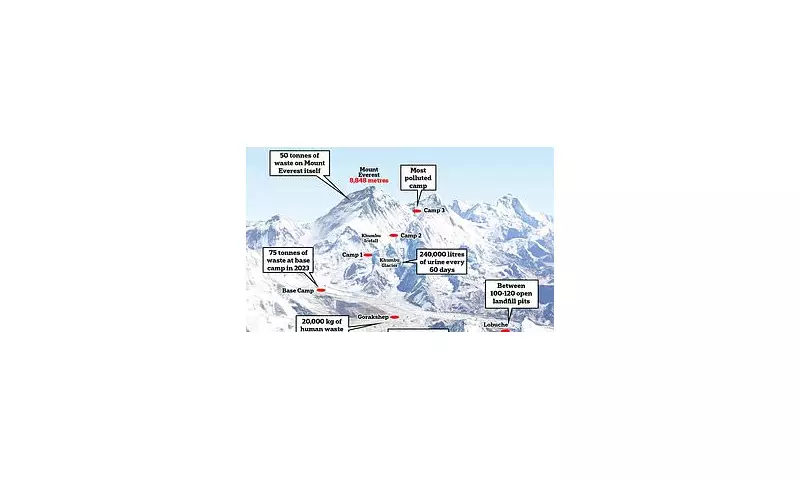

A 2020 scientific paper estimated that 50 tonnes of solid waste may have been left on Everest itself over the past 60 years. The Nepalese Army removed 34 tonnes in 2022 alone, up from 27.6 tonnes the previous year. The Spring 2023 season saw 75 tonnes of rubbish cleared from Base Camp, including 21.5 tonnes of human waste dumped in pits.

Mr Sherpa explained the core issue: 'From higher camps, people tend to bring back oxygen bottles only. Other things like tents and cans and boxes of packed foods and drinks are mostly left behind.' With no monitoring above the Khumbu Icefall checkpoint, there was little to stop this practice.

A New Strategy: Non-Refundable Fees and Rangers

In response, Nepalese officials are implementing a new rule. They will replace the refundable deposit with a non-refundable clean-up fee of around $4,000 per climber.

This money will establish a dedicated fund to finance a permanent checkpoint at Camp Two and pay for mountain rangers. These rangers will venture higher to properly monitor waste collection and ensure climbers are responsible for their own trash, which averages 12kg per person during a six-week expedition.

Mingma Sherpa, chair of the Pasang Lhamu rural municipality, welcomed the change, stating the Sherpa community had long questioned the old scheme's effectiveness. 'We are not aware of anyone who was penalised for not bringing their trash down,' he said. The new fund will finally enable systematic clean-up and monitoring work.

The move highlights the immense challenge of protecting one of the planet's most iconic yet vulnerable landscapes from the impact of commercial mountaineering and tourism.