For centuries, the legendary tale of Hannibal marching his war elephants across the treacherous Alps has captivated historians and military strategists alike. Now, archaeologists have unearthed a remarkable piece of evidence that could transform this ancient story from historical account to proven fact.

The Discovery in Cordoba

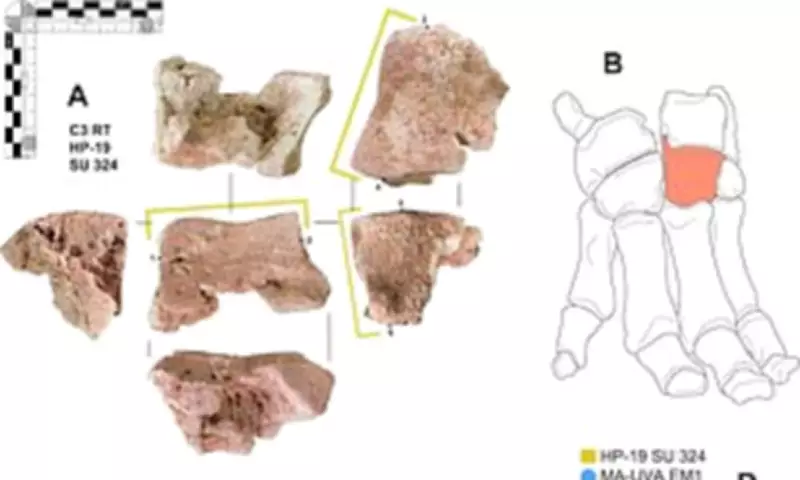

In 2020, during excavations beneath a consulting room at Cordoba Provincial Hospital in Spain, archaeologists made a startling discovery. Buried within the archaeological layers, they found a single, worn bone measuring approximately 10 centimetres cubed. After careful analysis, researchers identified this fragment as a carpal bone from the right forefoot of an elephant.

Scientific Analysis and Dating

Despite the bone's poor preservation, which prevented DNA extraction to determine the exact species, archaeologists employed sophisticated comparative techniques. They meticulously compared the ancient fragment with modern elephant bones and mammoth specimens, confirming its origin as elephantine. Crucially, researchers managed to carbon date a tiny sample from the bone, placing the animal's death between the late fourth and early third centuries BC. This timeframe aligns perfectly with the Second Punic War, which raged from 218 to 201 BC.

Historical Context of Hannibal's Campaign

The Second Punic War represents one of antiquity's most dramatic conflicts, pitting the Roman Republic against the Carthaginian Empire. Hannibal Barca, the Carthaginian general, executed one of military history's most audacious maneuvers by leading his army from Spain, through modern-day France, and across the Alps into Italy's vulnerable northern regions.

Historical accounts describe Hannibal's force comprising over 30,000 infantrymen, 7,000 cavalrymen, and approximately 37 war elephants. These specially trained African forest elephants, often armored for battle, served as living tanks capable of trampling enemy formations and creating psychological terror among Roman legions.

The Archaeological Site's Significance

The discovery location holds particular importance. Cordoba sits along Hannibal's presumed route through Spain toward the Alps. The excavation site corresponds to the ancient 'oppidum of Corduba,' a fortified settlement occupying a strategic terrace above the Guadalquivir River. Archaeologists documented a destruction layer at this location consistent with military conflict during the Second Punic War period.

Beyond the elephant bone, researchers uncovered compelling supporting evidence including twelve spherical stone balls used as artillery ammunition, heavy arrowheads associated with siege weapons called 'scorpia,' and coins minted in Cartagena between 237 and 206 BC. Together, these findings strongly suggest Carthaginian military activity at the site during Hannibal's campaign.

Evaluating Alternative Explanations

The research team, publishing their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, carefully considered alternative explanations for the bone's presence. While theoretically possible that the fragment arrived through trade routes, researchers note its small size and unremarkable appearance would have offered little value to traders. The most plausible explanation remains that the bone originated from one of Hannibal's war elephants, potentially killed during military operations against the oppidum of Corduba.

Broader Implications for Historical Understanding

This discovery represents potentially the first direct physical evidence supporting ancient accounts of war elephant use during Classical Antiquity in Western Europe. As the researchers note in their paper, 'The carpal of the elephant from Colina de los Quemados in Cordoba may constitute one of the scarce instances of direct evidence on the use of these animals during Classical Antiquity, not only in the Iberian Peninsula but also in Western Europe.'

The Carthaginian Empire, centered around ancient Carthage on the Gulf of Tunis, reached its zenith during the fourth century BC, establishing a mercantile network stretching from northern Europe to western Africa and Asia. Despite their historical significance, relatively little physical evidence survives from Carthaginian civilization, as most records were destroyed following Rome's victory in the Third Punic War in 146 BC.

This single elephant bone, therefore, offers a rare tangible connection to one of history's most legendary military campaigns, potentially confirming details that have survived only through written accounts, artistic depictions, and coin imagery for over two millennia.