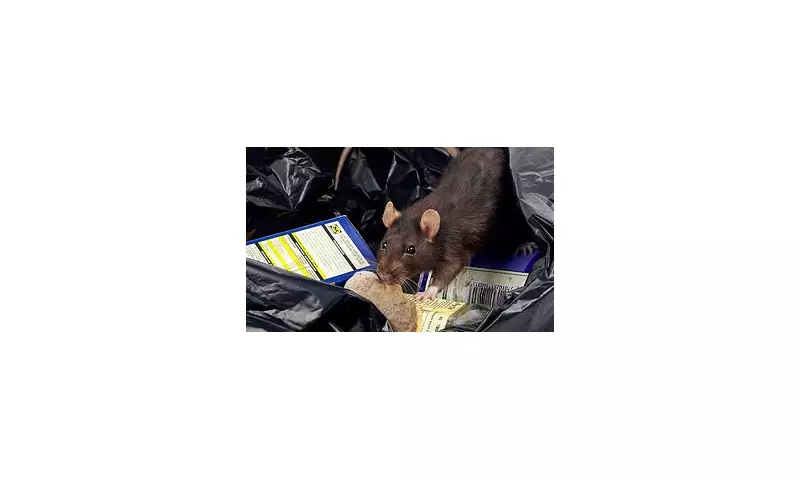

Complaints about rats made to local authorities in Scotland have reached a staggering high, with nearly 20,000 reports logged in a single year. The surge is being directly linked by opposition parties to severe cuts in council budgets, particularly for essential street cleaning services.

A Growing Urban Infestation

Data obtained by Scottish Labour reveals that 19,752 complaints about rats were made across Scotland in the 2024/25 period. This marks a significant 12.7% increase from the 17,528 reports made the previous year. The figures represent an average of 54 complaints every single day, painting a picture of a worsening rodent problem in urban areas.

The city of Glasgow is bearing the brunt of the issue. Alone, it accounted for 10,840 rat complaints last year. This is a 19.6% rise from 2023/24 and a shocking 50.2% increase compared to the 2020/21 figures. The city's unenviable reputation as a rodent hotspot was cemented back in 2021 when it was declared Scotland's rat capital, with estimates suggesting a population of 1.3 million rats.

Funding Cuts and Political Blame

The spike in complaints coincides with a period of intense financial pressure on local councils. Scottish Labour highlighted that expenditure on street cleaning has plummeted from £150.1 million in 2010/11 to just £98.3 million in 2024/25. This drastic reduction in resources is seen as a primary driver behind the proliferation of litter and, consequently, rodents.

Mark Griffin, Scottish Labour's local government spokesman, launched a scathing attack, stating: ‘Glasgow is a world-class city but we can all see how badly it is being let down... leaving us with litter on the streets and rats running riot.’

Public satisfaction reflects the growing crisis. Across Scotland, adult satisfaction with street cleaning fell to 58%, while in Glasgow it hit a dismal low of 37% – the poorest scores recorded since 2013/14.

Council Response and Worker Safety

Despite the alarming data, some council leaders have downplayed the health risk. SNP council leader in Glasgow, Susan Aitken, suggested the problem was one of ‘greater visibility’ rather than a genuine increase in the rodent population. Meanwhile, Public Finance Minister Ivan McKee distanced the Scottish Government, stating that funding for waste services is ‘a matter for local authorities’.

The situation has serious implications for frontline workers. Council refuse collectors in Glasgow have reported being attacked and bitten by rats, with some incidents requiring hospital treatment. Unions have warned of the growing danger for several years.

A spokesman for Glasgow City Council offered a pragmatic, if grim, perspective: ‘Rats can unfortunately be a fact of life in an urban environment. Thankfully the vast majority of Glasgow’s 300,000-plus homes will be completely unaffected by rodents at any one time because appropriate environmental controls are already in place.’

The stark divide between the statistical evidence of a rising problem and the official response suggests the debate over public health, funding, and urban cleanliness in Scotland's largest city is far from over.