Thamer and Faten, originally from Iraq, are confronting the stark reality of deportation from Sweden, a country where their third child was born. This couple, along with numerous other families, find themselves caught in the tightening grip of Sweden's increasingly stringent immigration policies, despite having built lives, learned the language, and contributed to society for many years.

A Life in Limbo: The Human Cost of Policy Shifts

Sofiye, who arrived from Uzbekistan in 2008, exemplifies the precarious situation facing many long-term residents. For over a decade, she built a stable life in a Stockholm suburb, working for the municipality in home help, learning Swedish, and raising her children within the Swedish school system. Her youngest son is Swedish-born, and her eldest, Hamza, knows no other home. However, after four unsuccessful asylum applications, she lost her right to work three years ago and now lives under a deportation order, residing in an asylum return centre near Arlanda airport with two of her children.

The stress has taken a severe toll on Sofiye's health. She reports sleeping only one or two hours a night, suffering from loss of appetite, and experiencing frequent vomiting due to anxiety. "I don't know physically, mentally what I should do," she confessed, highlighting the profound psychological impact of living in constant uncertainty.

Government Policy: A Shift Towards Restriction

The centre-right Swedish government, supported by the far-right Sweden Democrats, has implemented a series of measures aimed at reducing asylum numbers and prioritising labour immigration. Recent data shows Sweden received its lowest level of asylum seekers since 1985, a trend the government celebrates as creating "better conditions for successful integration." However, this shift has left thousands of well-established individuals and families facing removal.

Key policy changes include placing asylum seekers in reception centres rather than individual accommodation, offering "repatriation grants" for voluntary departure, and introducing stricter conditions for citizenship and family reunification. Applicants must now prove identity through in-person visits and provide extensive documentation. Additionally, committing a crime can result in deportation for non-citizens, with 440 people subjected to criminal deportations in 2025.

"If you do not want to become part of this community, you should not come to Sweden," the government has stated, marking a dramatic departure from the more welcoming stance of previous administrations. In 2014, then Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt urged Swedes to "open your hearts" to newcomers during a surge in arrivals from the Middle East.

The Abolition of 'Track Changes': A Critical Blow

One particularly damaging change, according to support workers, is the abolition of "track changes." This rule, enacted abruptly in April, prevents individuals with rejected asylum applications from applying for residence permits, even if they have been working in Sweden. It also blocks those with existing work permits from extending them. This decision is estimated to put 4,700 people integrated into Swedish society at risk of deportation.

Nannie Sköld, a counsellor at Stockholm Stadsmission's Who Am I Tomorrow? project, which provides legal and psychosocial support, noted the despair among those affected. "People who are well integrated and established in Sweden are asking: 'What else could I have done?'" she said. Many express disbelief that following all the rules still leaves them vulnerable to removal.

Life in Return Centres: Hardship and Fear

The asylum return centres, part of a plan to house an estimated 11,000 asylum seekers in coming years, present significant challenges. While the facility near Arlanda is "open," allowing residents to come and go, logistical difficulties and financial constraints mean many survive on just a few kronor daily. Shared spaces can feel unsafe, particularly for LGBTQ asylum seekers, and the environment is described as tough for children.

Mental health issues are rampant among residents due to their precarious circumstances. "There is a lot of fear, a lot of anxiety," Sköld explained. "People who have received a deportation order fear being deported any day."

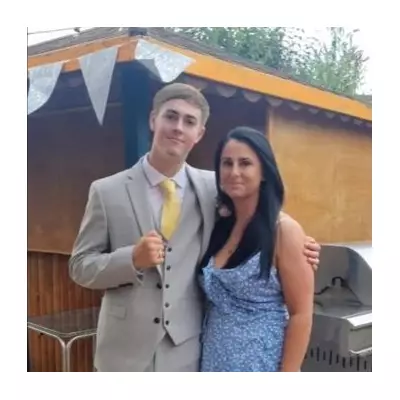

Individual Stories: Thamer and Faten's Plight

Thamer and Faten arrived from Iraq on work visas with their two sons, now aged 20 and 16. Their third son was born in Sweden in 2021. Despite Thamer's fluency in Swedish and his sons' willingness to work, the family faces deportation after their asylum applications were denied and work visas expired. Thamer, 52, expressed frustration, noting he was offered a job as a car mechanic but could not accept it due to his expired visa. "Sweden wants men and I have three. Can they not make use of them?" he asked.

Compounding their fear is a threat from a criminal organisation in Iraq that has warned of harm to their children if they return. "I am not a criminal," Thamer asserted, questioning what more he could do to prove his worth to Swedish authorities.

The Swedish migration agency stated it is "working to ensure that the reception and return centres are safe for everyone staying there, with particular consideration given to children and other vulnerable groups, such as LGBTQ persons." However, it declined to comment on individual cases.

As Sweden approaches a general election next year, observers note that the hardline stance is unlikely to change, with even opposition parties embracing similar policies. For families like Thamer and Faten's, and individuals like Sofiye, the future remains uncertain, their lives suspended between integration and expulsion.