The US state of New Mexico has initiated a major and costly environmental project, starting work to clean up five of the most dangerous abandoned uranium mines that threaten the health of nearby residents.

A Legacy of Contamination and a New Cleanup Plan

Following a 2022 state law mandating a remediation strategy, the New Mexico legislature allocated $12 million last year to begin addressing a staggering legacy of 1,100 mines and milling sites. The initial phase focuses on five priority locations: Schmitt Decline, Moe No. 4, Red Bluff No. 1, Roundy Shaft, and Roundy Manol.

Contractors, alongside state employees, are expected to make significant progress by June 2026, according to a progress report from the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED). This is the date when the initial funding is projected to be exhausted.

Immediate Risks to Human and Environmental Health

The selected sites present acute dangers. NMED communications director Drew Goretzka revealed that living near the Moe No. 4 mine for one year would expose a person to radiation equivalent to 13 years of normal background exposure. This site is particularly concerning as it drains into the San Mateo Creek, a waterway suspected of uranium contamination.

Goretzka also highlighted the physical peril of open mine shafts at some locations, which pose a falling risk to both humans and animals. The primary health threats, however, come from chronic exposure. Inhalation of contaminated dust and ingestion of polluted groundwater from private wells are key pathways for radiation to enter the body.

"While radiation readings may be relatively low at smaller sites, chronic exposure over long periods of time may present an increased hazard to nearby residents," Goretzka stated.

A Long-Overdue Response for Navajo Communities

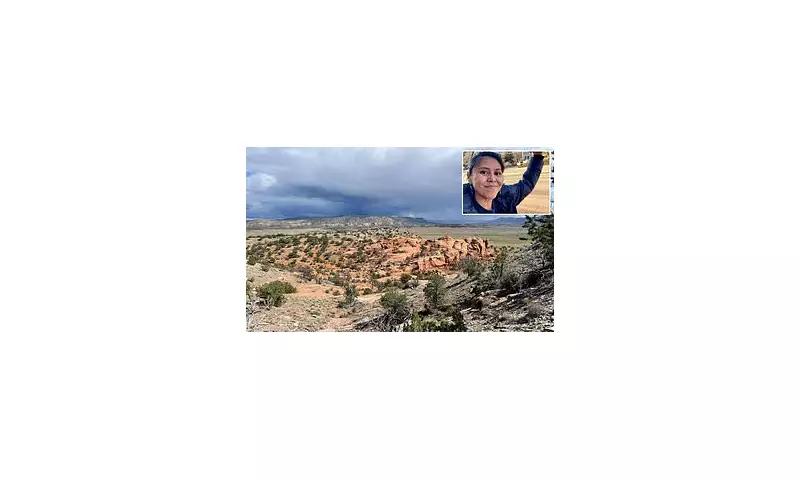

All five mines are situated in McKinley County, where over three-quarters of the population are Native American. The northwestern part of the county overlaps with the Navajo Nation, which extends into Arizona and Utah. For residents like Teracita Keyanna, 44, who grew up near two mines and a mill, the cleanup is long overdue.

"It's about time," Keyanna said, pointing to unexplained health issues in her community, including diabetes and liver cirrhosis among neighbours who led otherwise healthy lives. "These issues have been overlooked for way too long. The impact uranium has had on some of these communities is heartbreaking."

The historical context is grim. Large-scale uranium mining began in New Mexico in the late 1940s. The industry declined after the catastrophic 1979 Church Rock spill, which released 1.23 tons of radioactive tailings into the Puerco River, contaminating the Navajo Nation and harming livestock.

Decades later, the health impacts persist. The Navajo Birth Cohort Study found that pregnant Navajo women have much higher levels of uranium in their bodies than the average American. Alarmingly, nearly 92% of babies born to these mothers also had detectable uranium levels, with associated higher rates of developmental delays.

The Daunting Scale and Cost of Full Remediation

While the start of cleanup is welcomed, activists stress it is only a beginning. Of 261 abandoned mines identified by the state's Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, at least half have never seen any cleanup work.

Leona Morgan, a longstanding Navajo anti-nuclear activist, called the current effort "just scratching the surface." NMED analysts estimate a complete remediation of all sites would cost hundreds of millions of dollars, with a University of New Mexico study suggesting the cost could be "infinite" due to uranium dust being ingrained in the soil.

Morgan believes federal involvement and funding are essential for a successful, comprehensive cleanup. For now, NMED has begun on-site surveys, environmental sampling, and community engagement at the five targeted mines.

"We're hoping that we can show the public that we are going to do the right thing," said Miori Harms, NMED's uranium mine reclamation coordinator. The department aims to demonstrate progress to secure funding for the many years of work that lie ahead.