As the nation approaches the 80th anniversary of D-Day, a centenarian Jewish veteran who fought on the beaches of Normandy has delivered a devastating verdict on contemporary Britain, suggesting the hard-won victory over Adolf Hitler feels like a 'waste of time'.

A Life of Service, A Present of Despair

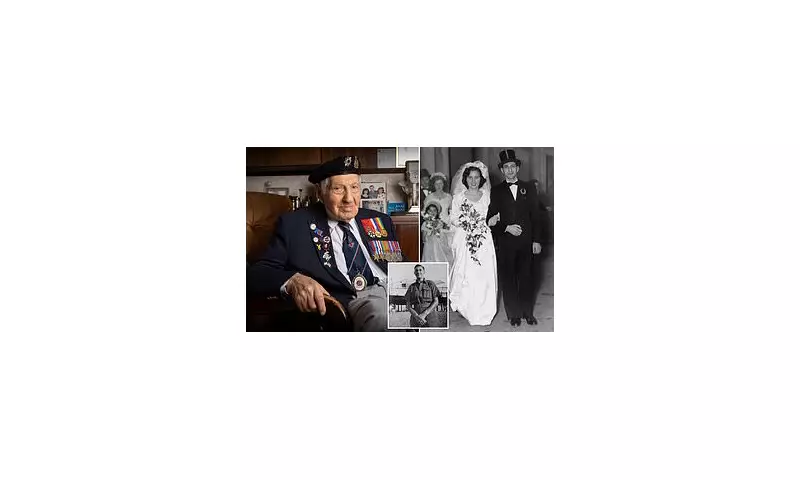

Mervyn Kersh, who will turn 101 in December, spoke with palpable despondency from his north London home. The recipient of France's Legion d'Honneur and praised by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson for educating the young, Mr Kersh now lives alone following the death of his beloved wife, Betty, in 2018.

His profound disillusionment echoes that of fellow centenarian veteran Alec Penstone, who recently told ITV's Good Morning Britain that the sacrifice of his fallen comrades 'wasn't worth' it, declaring Britain 'a darn sight worse' now than during the war.

'I think it [the war] was a waste of time,' Mr Kersh stated bluntly. He mourned the loss of the wartime spirit where 'everyone mucked in' to help one another, a camaraderie he believes has vanished from modern society. 'You don't get that now, no,' he lamented.

Confronting Crises: Immigration and a 'Lack of Leadership'

Mr Kersh pinpointed several issues fuelling his pessimism. While having 'no objection' to genuine refugees, he highlighted the ongoing Channel migrant crisis, with nearly 40,000 crossings recorded so far this year. He expressed concern that new arrivals often lack understanding of Britain's history and moral foundations.

His sharpest criticism, however, was reserved for the nation's political leaders. He contrasted today's politicians with figures like Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher. 'They led,' he asserted. 'They didn't just try to keep the job to the next day... They believed what they were trying to put over.'

He accused successive governments of failing the country, with promises routinely broken upon 'looking at reality'. Furthermore, he argued passionately that national defence should be the paramount spending priority, even if it means diverting funds from elsewhere. 'Defence must come first,' he insisted.

From D-Day to Belsen: A Young Soldier's Journey

Born in Brixton in 1924, Mervyn Kersh was just 18 when he was conscripted into the Army's Ordnance Corps in 1943. He landed on Gold Beach on June 9, 1944, three days after the initial D-Day assault, eager to play his part in defeating the Nazis.

His war took him through France, Belgium, and into Germany. In May 1945, stationed in Celle, he visited the nearby Bergen-Belsen concentration camp shortly after its liberation. Though barred from entering due to disease, he spoke to emaciated survivors and, unaware of the dangers, handed out his chocolate rations. 'I spoke to whoever could speak English... Not a very happy state,' he recalled of the encounter with the horrors of the Holocaust.

With Japan's surrender after the atomic bombs, his deployment to the Far East was cancelled, and he instead served six months in Egypt, where he was reunited with his brother Cyril.

Post-War Life, Love, and Legacy

Demobilised in late 1946, Mr Kersh struggled to find his footing in a peacetime economy, feeling his education and career path had been irrevocably disrupted by the conflict. His fortunes changed at a New Year's Eve party in 1948, where he met Betty. In a remarkable twist, her twin sister, Esta, went on to marry Mervyn's brother, Cyril. The two couples were inseparable for decades, marrying in the same year, 1949, and raising families side-by-side.

Now a grandfather and great-grandfather, Mr Kersh continues to share his experiences in schools. He notes a lack of discipline in modern youth and observes that children often 'repeat what they've heard' rather than think for themselves. His mission is to impart the gravity of what his generation fought for, a cause he now fears has been undermined by the country's current trajectory.

Looking back on his service, he said, 'It was very satisfying to know that I had done what I could to end it.' Yet, looking at Britain today, that satisfaction is tragically tempered by a belief that the nation he helped save has since been lost to a different set of crises.